A few weeks ago, during a 9th-grade class meeting at Princeton Day School (PDS), a student raised her hand and asked, “Can we use ChatGPT to help us get started on an assignment?”

A few weeks ago, during a 9th-grade class meeting at Princeton Day School (PDS), a student raised her hand and asked, “Can we use ChatGPT to help us get started on an assignment?”

We hear versions of that question often. Students are navigating a learning environment that has evolved almost overnight, and they are now trying to understand how AI fits into their academic work and daily routines. They are curious, sometimes uncertain, and consistently eager to experiment. What they need from us is deliberate guidance that helps them use these tools in ways that deepen, rather than diminish, their own thinking.

That need quickly shaped our initial approach to these new challenges. As AI tools began accelerating, we brought faculty, technology staff, and academic leaders together to consider what this shift might mean for teaching and learning. Those conversations helped us move past the initial uncertainty — the fear of losing traditional assessments or of not being able to distinguish student work from machine output — and toward a more essential question: What do students need to understand now in order to thrive in the future?

That need quickly shaped our initial approach to these new challenges. As AI tools began accelerating, we brought faculty, technology staff, and academic leaders together to consider what this shift might mean for teaching and learning. Those conversations helped us move past the initial uncertainty — the fear of losing traditional assessments or of not being able to distinguish student work from machine output — and toward a more essential question: What do students need to understand now in order to thrive in the future?

Nationally, discussions about AI still focus heavily on detection and restriction. But those questions alone don’t serve students well. Detection tools are inherently unreliable, and bans don’t teach judgment or responsibility. Instead, we’ve focused on building AI literacy as part of a whole-school approach. In advisory, class meetings, and informal conversations, students grapple with ethical dilemmas, bias in training data, intellectual property, misinformation, and what it means to maintain agency when working with AI. They practice weighing not just whether they can use AI, but whether they should — guided by three questions we use school-wide: Is it safe? Is it ethical? Is it effective?

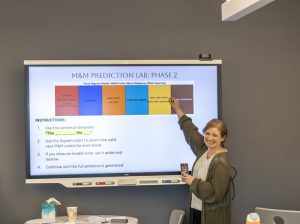

Examples from across divisions show how AI is becoming part of thoughtful learning design. In a Middle School humanities class, students document how they used AI during research — why they consulted it, how they evaluated its suggestions, and when they chose to go in a different direction. In English, seniors studying Circe used AI to surface passages from ancient texts they might otherwise miss, expanding their interpretive options while ensuring they drove the analysis themselves. In math, students applied statistical models to historical hurricane damage and then used AI to identify potential trends — only after cross-checking results against original data to test accuracy. In each case, the goal is not simply to use AI, but to understand when and how it strengthens thinking.

Examples from across divisions show how AI is becoming part of thoughtful learning design. In a Middle School humanities class, students document how they used AI during research — why they consulted it, how they evaluated its suggestions, and when they chose to go in a different direction. In English, seniors studying Circe used AI to surface passages from ancient texts they might otherwise miss, expanding their interpretive options while ensuring they drove the analysis themselves. In math, students applied statistical models to historical hurricane damage and then used AI to identify potential trends — only after cross-checking results against original data to test accuracy. In each case, the goal is not simply to use AI, but to understand when and how it strengthens thinking.

In the Lower School, AI literacy is introduced conceptually through our digital citizenship curriculum. Our youngest students begin learning how technology processes information, how to question what they see, and how to notice when “something doesn’t feel right.” These early habits of mind become the groundwork for deeper engagement later on. As students move through Middle and Upper School, they learn to treat AI as a thinking partner rather than a shortcut, and that understanding increasingly shapes how our teachers design learning experiences.

Many teachers are adapting their practice with this mindset. Rather than preventing AI use, they are designing learning experiences in which human judgment, context, and interpretation remain essential. When planning a project, faculty think carefully about if and where AI belongs — whether as light brainstorming support or a deeper model interaction — and select an approach that preserves meaningful engagement and the right amount of productive struggle. Just as importantly, we want students to develop a felt sense of learning: when to push through uncertainty, when to collaborate with peers, and when turning to AI would short-circuit the reasoning we want them to develop.

Many teachers are adapting their practice with this mindset. Rather than preventing AI use, they are designing learning experiences in which human judgment, context, and interpretation remain essential. When planning a project, faculty think carefully about if and where AI belongs — whether as light brainstorming support or a deeper model interaction — and select an approach that preserves meaningful engagement and the right amount of productive struggle. Just as importantly, we want students to develop a felt sense of learning: when to push through uncertainty, when to collaborate with peers, and when turning to AI would short-circuit the reasoning we want them to develop.

To deepen the conversation, we introduced a new interdisciplinary Upper School course that closely examines AI’s social and ethical dimensions. Students explore big questions — Can AI be trusted? Can we afford AI? — and consider them through both factual evidence and their own values and hopes for the future. Our goal is to help them develop a sense of agency, understanding that their choices and voices will shape how AI affects the world they’re growing up in.

Our efforts also connect to a broader professional conversation. Through regional educator networks and by hosting the New Jersey Association of Independent Schools Technology and Innovation Conference this past summer, which focused heavily on AI’s impact on teaching and learning, we are advancing the dialogue on thoughtful, developmentally appropriate integration.

If anything, AI has made the essential human skills students need even more visible. They must be able to make ethical choices, interpret complex information, evaluate claims, collaborate and empathize with others, and explain the reasoning behind their conclusions. Thinking doesn’t happen only in isolation; it happens dynamically through dialogue, shared inquiry, and the kinds of human engagement that shape understanding.

Colleges and employers are already expecting graduates to use AI thoughtfully. Some university admissions offices now ask applicants to generate an AI-assisted draft and then critique it. Many workplaces expect young adults to understand not only how AI can support their thinking, but when to question or override it. Our students will enter that world, not the one we grew up in. Preparing them means giving them opportunities to experiment and reflect now, while the stakes are low.

We’re still learning, and we expect that to continue. New tools appear constantly, each raising new questions. But the heart of our work remains steady: helping students understand when AI can broaden their thinking and when they need to rely on their own insight. We want them to leave PDS not just comfortable with technology, but confident in the unique value of their own minds.

We’re still learning, and we expect that to continue. New tools appear constantly, each raising new questions. But the heart of our work remains steady: helping students understand when AI can broaden their thinking and when they need to rely on their own insight. We want them to leave PDS not just comfortable with technology, but confident in the unique value of their own minds.

We are grateful that this work happens in partnership with students who are curious and open, with teachers who are willing to rethink long-standing practices, and with families who share observations and questions from home. AI may change the tools students use, but it doesn’t change what we hope for them: that they think with clarity, lead with compassion, and use their talents to strengthen their communities. Those qualities will matter long after today’s technologies evolve into something new. They are also the qualities that will help our students shape the world they are preparing to enter.

To learn more about Princeton Day School’s approach to AI education, visit pds.org/ai.

Lauren Ledley is the Director of Academic Technology and Institutional Research at Princeton Day School. She joined the faculty in 2013 as a Middle and Upper School history teacher and has since dedicated her work to helping PDS grow as a learning community. Today, she supports academic technology across PK–12 and leads the school’s institutional research and artificial intelligence efforts. In this role, Lauren helps PDS listen closely to the voices of students, families, and employees, using feedback and data to strengthen the connection between the school’s values and everyday experience. She also guides the community in navigating AI thoughtfully, ensuring it is used ethically, safely, and in ways that encourage curiosity, creativity, and deep learning. Lauren holds an A.B. in Anthropology, magna cum laude, from Princeton University, and an M.S.Ed. in School Leadership from the University of Pennsylvania.