Princeton is in the middle of a quiet but profound reset in how we own, tax, and use our homes. Recent changes to LLC rules, state tax policy, and local accessory dwelling unit (ADU) ordinances are reshaping everything from who can afford to stay here to what our neighborhoods look like. While the details are technical, the underlying concern for many residents is simple: can we preserve Princeton’s character and fairness while adapting to economic reality?

Princeton is in the middle of a quiet but profound reset in how we own, tax, and use our homes. Recent changes to LLC rules, state tax policy, and local accessory dwelling unit (ADU) ordinances are reshaping everything from who can afford to stay here to what our neighborhoods look like. While the details are technical, the underlying concern for many residents is simple: can we preserve Princeton’s character and fairness while adapting to economic reality?

At the ownership level, many small landlords and homeowners who hold property in LLCs are encountering a new level of scrutiny. The federal Corporate Transparency Act, effective January 1, 2024, requires most LLCs to disclose their “beneficial owners” to the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). LLCs formed before 2024 generally must file a beneficial ownership report by January 1, 2025, while new entities created in 2024 have 90 days, and those formed from 2025 forward have 30 days. This applies squarely to the single‑property LLCs often used in Princeton to hold a family rental, a student house, or an investment duplex. Large employers with 20 or more U.S. employees, a physical office, and over $5 million in U.S. revenue may be exempt, but the typical local landlord is not.

For investors, this feels like new paperwork layered on top of already complex real‑estate compliance. Yet many residents see a different benefit. By requiring disclosure of the real people behind ownership structures, the law makes it harder for anonymous entities to quietly accumulate homes in a tight market without any public visibility. In a town where neighbors regularly ask who is buying on their block—and whether those buyers will live here or treat the house as a commodity—this transparency aligns with a strong local preference for accountability.

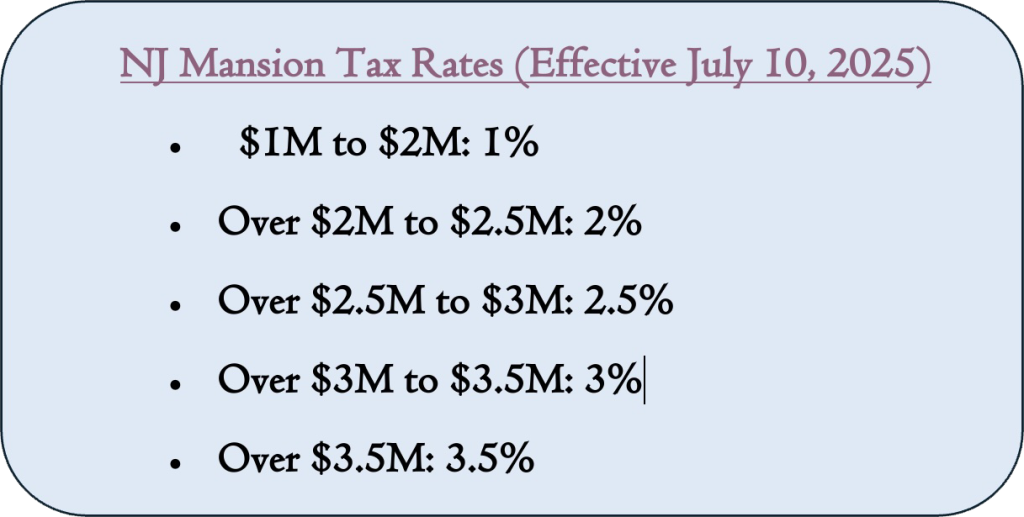

New Jersey’s recent tax changes pull in the same direction of asking more from the top of the market while trying to protect those who feel squeezed by rising bills. Beginning July 10, 2025, the state’s so‑called “mansion tax,” formally the Realty Transfer Fee, was overhauled for high‑value transactions. Previously, buyers paid a flat 1 percent on properties over $1 million. Now, for properties at or above that threshold, the fee is the seller’s responsibility, and transfers of $2 million or more are subject to a progressive rate schedule that can reach as high as 3.5 percent on sales above $4 million. Crucially, these higher rates apply to the entire sale price, not just the dollars above a given tier. In a town where seven‑figure sales are common, that is not an abstract policy tweak; it is a meaningful change to the economics of selling a high‑end home or commercial property.

New Jersey’s recent tax changes pull in the same direction of asking more from the top of the market while trying to protect those who feel squeezed by rising bills. Beginning July 10, 2025, the state’s so‑called “mansion tax,” formally the Realty Transfer Fee, was overhauled for high‑value transactions. Previously, buyers paid a flat 1 percent on properties over $1 million. Now, for properties at or above that threshold, the fee is the seller’s responsibility, and transfers of $2 million or more are subject to a progressive rate schedule that can reach as high as 3.5 percent on sales above $4 million. Crucially, these higher rates apply to the entire sale price, not just the dollars above a given tier. In a town where seven‑figure sales are common, that is not an abstract policy tweak; it is a meaningful change to the economics of selling a high‑end home or commercial property.

At the same time, the state is rolling out and fine‑tuning property‑tax relief programs aimed at seniors and moderate‑income households. The Stay NJ program, now beginning to issue payments, promises a reimbursement of 50 percent of property taxes—up to a $6,500 cap—for eligible homeowners aged 65 and older with incomes up to $500,000. These benefits are coordinated with ANCHOR and Senior Freeze payments, and many residents have begun receiving quarterly checks instead of lump sums, with an average first Stay NJ installment of about $637 statewide. For long‑time Princeton homeowners watching their assessments and municipal, school, and county levies climb, these programs are lifelines that help them stay in homes and neighborhoods they helped build.

The tension arises in how these statewide policies interact with Princeton’s own tax decisions. Recent municipal budgets have increased the local tax rate by about one cent per $100 of assessed value in successive years, adding over a hundred dollars annually to the municipal portion of the bill on a typical home assessed in the mid‑$800,000s. Residents understand that this revenue funds services they value—public safety, infrastructure, environmental initiatives—but they are also acutely aware that these increases stack on top of school and county taxes. In online forums and letters to the editor, a recurring theme is “tax fatigue”: a sense that even with state relief programs, the overall burden in Princeton remains among the highest in New Jersey.

This is where local tools like PILOT agreements and zoning choices become controversial. Princeton has used long‑term tax exemptions and payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) to make certain multifamily and mixed‑use developments financially viable, especially when they include affordable units. Under recent ordinances, a project’s multifamily component can be subject to a negotiated service charge instead of conventional property taxes, while any single‑family homes on the same site remain fully taxable. Supporters argue that without these incentives, needed housing simply would not be built, and the town would fall short of its fair‑share obligations. Critics counter that diverting revenue from the standard tax structure can undercut school funding and shifts more of the load onto existing homeowners, who do not have access to similar deals.

Overlaying these fiscal questions is a set of land‑use reforms quietly changing what can be built on a typical residential lot. Princeton’s accessory dwelling unit (ADU) framework is one of the clearest examples. The zoning code now allows ADUs as subordinate units on one‑family properties, with size capped at the lesser of 800 square feet or 25 percent of the principal dwelling’s floor area, and somewhat higher limits—up to about 1,000 square feet—available when the ADU is income‑restricted for low‑ and moderate‑income households under state affordability rules. Detached ADUs must comply with accessory‑structure bulk standards and cannot exceed the size of the main house, and there are minimum separation requirements between the ADU and the primary dwelling. Parking requirements are intentionally modest, especially in walkable, transit‑served areas, reflecting a policy choice to remove barriers to small‑scale, “gentle” density.

Overlaying these fiscal questions is a set of land‑use reforms quietly changing what can be built on a typical residential lot. Princeton’s accessory dwelling unit (ADU) framework is one of the clearest examples. The zoning code now allows ADUs as subordinate units on one‑family properties, with size capped at the lesser of 800 square feet or 25 percent of the principal dwelling’s floor area, and somewhat higher limits—up to about 1,000 square feet—available when the ADU is income‑restricted for low‑ and moderate‑income households under state affordability rules. Detached ADUs must comply with accessory‑structure bulk standards and cannot exceed the size of the main house, and there are minimum separation requirements between the ADU and the primary dwelling. Parking requirements are intentionally modest, especially in walkable, transit‑served areas, reflecting a policy choice to remove barriers to small‑scale, “gentle” density.

Local organizations have framed these units not just as a housing tool but as part of Princeton’s climate and equity strategy. Sustainable Princeton, for example, highlights ADUs as a sustainable option that allows property owners to house extended family, caregivers, or renters without consuming new greenfield land, while making better use of existing infrastructure. For many residents, this aligns with a deeply held preference for solutions that fit the town’s established fabric—a converted garage or backyard cottage rather than a large new apartment block. In neighborhood discussions, you often hear support for ADUs as a way to help aging parents stay close or to create a manageable rental that helps defray property taxes.

Still, that support is not unconditional. Some neighbors worry about incremental pressures on street parking, privacy, and the feel of streets originally laid out for strictly single‑family use. Questions arise about enforcement: will illegal conversions proliferate, will owner‑occupancy rules be followed, and how will short‑term rentals be regulated. Princeton’s 2025 short‑term rental ordinance responds to part of this by requiring that, when an ADU is used as a short‑term rental, the main dwelling must be the principal residence of the owner or a long‑term tenant, and by imposing insurance, registration, and fee requirements on such rentals. That approach reflects a dominant local sentiment: new flexibility is acceptable, but it should come with guardrails that prevent investor‑driven “mini‑hotel” clusters from eroding neighborhood cohesion.

Still, that support is not unconditional. Some neighbors worry about incremental pressures on street parking, privacy, and the feel of streets originally laid out for strictly single‑family use. Questions arise about enforcement: will illegal conversions proliferate, will owner‑occupancy rules be followed, and how will short‑term rentals be regulated. Princeton’s 2025 short‑term rental ordinance responds to part of this by requiring that, when an ADU is used as a short‑term rental, the main dwelling must be the principal residence of the owner or a long‑term tenant, and by imposing insurance, registration, and fee requirements on such rentals. That approach reflects a dominant local sentiment: new flexibility is acceptable, but it should come with guardrails that prevent investor‑driven “mini‑hotel” clusters from eroding neighborhood cohesion.

Taken together, these developments show a community trying to thread a narrow needle. Princeton residents broadly value fairness, transparency, and inclusion, but they also prize the town’s historic character, walkability, and strong public institutions. LLC transparency rules respond to concerns about anonymous investors; mansion‑tax changes and PILOT scrutiny reflect a desire that those benefiting most from Princeton’s high values contribute accordingly; and ADU reforms represent a cautious bet on small‑scale growth over large‑scale upheaval.

In this moment, factual policy changes are doing much of the work that opinions used to carry. Residents are reading the fine print of tax tables and zoning codes because they sense that the stakes—for who can stay, who can come, and what Princeton looks like in twenty years—are written there.

Tim Crew was born and raised in Princeton Junction. He brings a local’s perspective and a global business background to the Terebey Relocation Team. After graduating from West Windsor–Plainsboro High School South, he attended the University of Michigan before moving to London, where he worked in strategy and commercial sales for a leading sports marketing firm. There, he helped major rights holders like the NFL, Formula 1 teams, and top European football clubs decide which assets to sell, how to position them, and which audiences to target, experience that now shapes how he analyzes and markets homes. Today, Tim leverages that data‑driven, strategic approach to pricing and presentation, along with an efficient back‑end system he built for the team, to help clients navigate a competitive NJ market. The Terebey Relocation Team has operated locally for more than 40 years and has been the number‑one team in Mercer County by homes sold over the past two years, combining deep roots with a modern, results‑focused approach.