Princeton University (PU) made national headlines in late June, as it officially removed the name of Woodrow Wilson from its School of Public and International Affairs and its residential college. Though he was a distinguished President of PU who went on to become the 28th President of the United States and a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Board of Trustees reconsidered a determination it made in 2016 and decided he should no longer be the namesake for its school due to his racist thinking and policies.

Princeton Public Schools (PPS) is now contemplating a similar situation as its Board of Education has been asked to consider if John Witherspoon, the 6th President of The College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, should be removed as the namesake for the town’s middle school. Whether Witherspoon’s record as both a slave owner and a man who educated free Black men disqualifies him or allows him to keep the naming rights is now being debated.

Princeton Public Schools (PPS) is now contemplating a similar situation as its Board of Education has been asked to consider if John Witherspoon, the 6th President of The College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, should be removed as the namesake for the town’s middle school. Whether Witherspoon’s record as both a slave owner and a man who educated free Black men disqualifies him or allows him to keep the naming rights is now being debated.

As heightened voices shout out against racism, The Hun School of Princeton (Hun) announced it is changing the name of its chief administrator. Jon Brougham has long been known as “Headmaster.” Merriam-Webster defines the term as “a man who is the head of a U.S. private school” but the use of the word “master” has sparked criticism. In a letter to Hun families, Brougham explained he’s been questioning it’s meaning for years, and a decision to change it finally came in June after students and staff petitioned that the title denotes negative connotations of race and gender. Like most other independent schools in our area, Brougham is now to be referred to as “Head of School.”

As heightened voices shout out against racism, The Hun School of Princeton (Hun) announced it is changing the name of its chief administrator. Jon Brougham has long been known as “Headmaster.” Merriam-Webster defines the term as “a man who is the head of a U.S. private school” but the use of the word “master” has sparked criticism. In a letter to Hun families, Brougham explained he’s been questioning it’s meaning for years, and a decision to change it finally came in June after students and staff petitioned that the title denotes negative connotations of race and gender. Like most other independent schools in our area, Brougham is now to be referred to as “Head of School.”

PU President Christopher Eisgruber explained in his message to the Princeton community that names shape the identity of a school. So, the schools remove their connections to names and words that are considered racist, but how does that progress anti-racism?

“When you change a name there are conversations,” explains Timothy Charleston, John Witherspoon (JW) Middle School’s new Assistant Principal who has been PPS Supervisor of Social Studies PreK-8 for the past six years and is one of the supporters of the petition to change his school’s name. “Forcing people to have a conversation about racism – that’s how we move ahead as a society.”

And the conversations, at least in Princeton, have begun. While streets here and around the country filled in protest against police brutality, demanding justice for the killing of George Floyd and declaring that Black Lives Matter, the school year was ending. Students and staff were home, contemplating the heavy world around them alone, due to remote learning. Only weeks remained until PPS Superintendent Steve Cochrane would retire on June 30th, but he felt an obligation to respond to the call.

And the conversations, at least in Princeton, have begun. While streets here and around the country filled in protest against police brutality, demanding justice for the killing of George Floyd and declaring that Black Lives Matter, the school year was ending. Students and staff were home, contemplating the heavy world around them alone, due to remote learning. Only weeks remained until PPS Superintendent Steve Cochrane would retire on June 30th, but he felt an obligation to respond to the call.

To begin to acknowledge any wrongs and to help process the emotions, PPS immediately sought the help of two longtime consultants to meet with its administrative team and help them begin to examine their roles regarding racism as both individuals and as an institution. Trauma expert, Dr. Tara Doaty, and Marceline DuBoise, who had conducted the district’s equity audit, met with Cochrane and his team as a group as well as separately with the administrators of color. Later in June, sessions were offered to all staff and to students from both JW Middle School and Princeton High School so they could learn from each other, have an opportunity to share what they need and move towards action.

Hun has also committed to listen to its faculty and students to move towards change and has recently held meetings with components of its student body, their families and staff to guide new initiatives. The Director of its Cultural Competency Committee, Otis Douce, has also been promoted to Director of Cultural Competency and Global Diversity as a member of the administrative team to help move them forward. Amongst his other projects, Douce has been the leader of Hun’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Summit for the past five years, designed to enlighten students about oppression and privilege and how they can be the ones to enact change.

Since the Amistad Bill was passed in New Jersey in 2002 there has been a requirement for schools to teach about African slave trade, slavery in America and about the contributions of African Americans on society. Those guidelines took history education a step further, but schools are now feeling a need to go beyond that to teach anti-racism and social activism.

“When we think about our mission of graduating students into the world so they can live lives of joy and succeed, we talk about math literacy, economic literacy, etc.” explains recently retired Superintendent Cochrane. “There should be a responsibility on the part of school systems to provide our students with racial literacy to navigate a racially complex world. If we’re not teaching that, we’re promoting racism by our silence.”

As the district analyzes new ways to incorporate racial literacy, Cochrane notes it shifted its focus in recent years to ensure there are a range of books by authors of different backgrounds and experiences being assigned and made available to students. In 2018 it also incorporated Princeton Choose, a book created by two former PHS students, to begin discussions on racial literacy by engaging 5th grade students in learning about different cultures. Preparedness for this kind of learning actually starts as early as kindergarten, through discussions about diversity, skin color, gender roles and making sure the imagery surrounding classrooms is not stereotypical.

Getting to know and understand each other is a key component of the Community Period established in 2019 at JW Middle School. By connecting people outside their typical social circles, and helping them know and understand each other, the administration hopes students will engage in active listening and become more socially aware. Charleston led one of the Community Period groups last year.

“We focused on looking at restorative practices and building that community, understanding where people are coming from,” he details. “We want to continue to try and incorporate that in the coming school year to an even greater degree.”

For older students, a Racial Literacy & Justice (RLJ) elective has been offered to grades 10-12 at Princeton High School since 2018. Teachers Dr. Joy Barnes-Johnson and Ms. Patty Manhart spent years working with students and other educators to create the class. To date, 70 students chose to take the course to discuss race history in the United States and explore racial domination and racial progress. It seems natural now a course such as this should become a requirement for all students, not just those that select it. But Cochrane believes PPS doesn’t yet have enough teaching teams with a deep level of understanding. Dr. Barnes-Johnson believes the community also needs to be more prepared.

“Race talk is difficult for people because of the unfortunate shame and guilt that comes with facing ones’ own biases. We want students to want to be antiracist in their thinking which is why we value the voluntary nature of the higher-level Racial Literacy & Justice course,” adds Barnes-Johnson. “The curriculum is not just a single class, textbook or activity. It includes disciplinary policies, resource allocations, staffing decisions and programs of studies that keep classes from being fully desegregated.”

Graduates of the RLJ elective are now being paired with peer group advisors in the high school so they can begin conversations around issues of race with freshman as they come in.

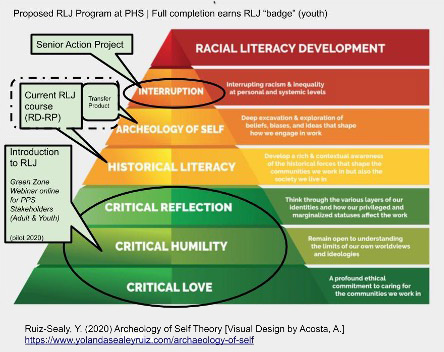

As another step forward, to expand the minds of educators about multicultural education and to create an opportunity for more students to engage in this learning, an online class is being created by Dr. Barnes-Johnson and Ms. Manhart. Based on Dr. Yolanda Ruiz-Sealy’s “Archeology of Self” model, the online course will be broken into three segments. Those taking all parts would be required to self-reflect, study racial literacy and share their learning.

As another step forward, to expand the minds of educators about multicultural education and to create an opportunity for more students to engage in this learning, an online class is being created by Dr. Barnes-Johnson and Ms. Manhart. Based on Dr. Yolanda Ruiz-Sealy’s “Archeology of Self” model, the online course will be broken into three segments. Those taking all parts would be required to self-reflect, study racial literacy and share their learning.

Educating staff in racial literacy is one component, but the administrators at PPS and Hun both share the ideal that growing the racial diversity amongst their staff is also essential. As of late June, PPS had hired 15 new teachers for the 2020-2021 school year. 10 of them are educators of color. An analysis of the student body was recently done in an attempt to understand the racial breakdown of each school with a goal to have its faculty more representative of its students. The district shared that currently 84% of its staff is white, yet the most recent data indicates nearly half of the student population is not.

NJ School Performance Report,

Princeton Public Schools Enrollment by Racial and Ethnic Group

| Racial and Ethnic Group | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

| White | 54.7% | 53.3% | 52.2% |

| Hispanic | 13.4% | 14.3% | 15.3% |

| Black or African American | 6.3% | 6.1% | 6.1% |

| Asian | 20.3% | 19.7% | 19.9% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Two or More Races | 5.1% | 6.4% | 6.4% |

Source: NJ Department of Education

Hun has not historically collected data on the racial identities of its students, but it is intensifying efforts to recruit and hire more diverse educators and leadership, citing this has been a priority but they must improve.

“Most of our efforts aim at broadening the pool of diverse candidates. We attend minority recruitment conferences and networking events, advertise openings at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and contact diversity offices of other universities to seek qualified candidates,” says Douce. “We have also recently created a fellowship program for teachers new to the profession that is focused on recruiting diverse graduates.”

Hun is additionally adding training for its current staff. It promises to examine the themes and content of its curriculum at all levels and is reviewing its policies and rules to ensure they are aligned with having a bias-free environment. A new anti-bias statement, written by students, is now being incorporated into the Princeton High School code of conduct as well.

To help its staff, parents and students process today’s situation and move forward, PPS has been compiling information to create an anti-racism resource page on the district website – another project started under Superintendent Cochrane. He since retired at the end of June and Interim Superintendent Barry Galasso officially started July 1st. But where one ended, the other plans to begin.

“Princeton Public Schools have been leaders in promoting equity and racial literacy and that tradition will continue to evolve,” states Galasso. “I’m looking forward to expanding and building on the district’s current curriculum to promote racial literacy.”

It’s been less than two months since the recent tragedies and enlightenment created an awareness to do better. The conversations have started. Time will tell their impact.

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!