According to Federal census records, in 1838 the twelve last known slaves were recorded in Princeton Township, NJ. As they and the slaves before them gained their freedom, they began to settle on Witherspoon Street. Through the 1800s, the Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood became home to Princeton’s Black community.

It was a segregated part of town. In 1858 the first school, exclusively for Black children, was created. Unwelcomed in most stores, restaurants, beauty parlors and bars in town, in the 1900s they built their own. In 1916, Princeton High School was integrated, but lower schools did not do so until 1948, when mandated by law.

In the 1930s, large numbers of African Americans were displaced, moved further from where many worked at the university to Birch Avenue, as downtown development took over their neighborhood. Though Princeton as a society has integrated through the years, many African Americans today contend the rising costs of housing pushes them out and that education and employment opportunities remain unequal.

Last month, thousands of locals gathered at the gates of Princeton University to protest racism, to demand better treatment of Blacks and that as a community we work harder to ensure all opportunities – housing, education and economic – be as available to them as to their neighbors of other races. The protests occurred at the same gates that had at one time been locked to keep out the nearby African American residents from town.

Last month, thousands of locals gathered at the gates of Princeton University to protest racism, to demand better treatment of Blacks and that as a community we work harder to ensure all opportunities – housing, education and economic – be as available to them as to their neighbors of other races. The protests occurred at the same gates that had at one time been locked to keep out the nearby African American residents from town.

The recent rallying cry led the municipal government to take a closer look at its role in enacting change. On June 8, 2020 Princeton Town Council passed a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis. It is a means for the municipality to assess internal policies and procedures and advocate for relevant ways to dismantle racism.

“It’s not like this was a sudden realization. We have been working to try to reverse the decades and centuries of problems,” explains Princeton Mayor Liz Lempert, noting the re-establishment of the Civil Rights Commission as a stand-alone advisory body in 2017.

Since the passing of the resolution, the Civil Rights Commission has been tasked with trying to find the right national framework on racial equity to guide municipal practice.

“I found it useful for other initiatives we have worked on to be plugged into a wider network. We can learn from other communities and they can learn from us. It helps what we’re doing here have a greater impact and vice versa,” adds Lempert.

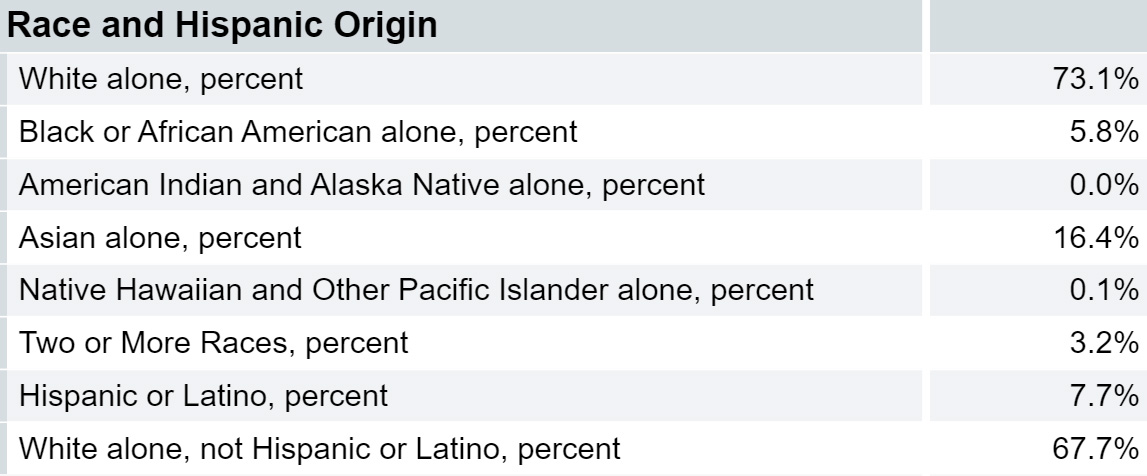

As a government entity, Princeton is trying to be more intentional in diversity and hiring. Though it remains largely Caucasian, the percentage of African Americans and Hispanics hired by Princeton is greater than those represented in the general population as compared to the 2019 Census numbers for Princeton:

Racial Demographics of Princeton Municipal Staff

| Percentage | # Employed | |||

| Caucasian | 78% | 201 | ||

| African American | 10% | 27 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 10% | 26 | ||

| Asian | 1% | 4 | ||

| 2 or more Races | 0.30% | 1 | ||

| Total Employed: 259 | ||||

2019 Census Numbers for Princeton, NJ

Source: United States Census Bureau, 2019

Source: United States Census Bureau, 2019

Lempert knows they can still do better. Employees are required to attend diversity training twice a year. To fill open roles, the municipality is advertising and recruiting with professional networks that will help diversify its candidate pool.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mayor notes racial disparities have become even more apparent with people of color in New Jersey being disproportionately hurt by both the medical and financial aspects of the pandemic. To help, the town is offering quarantine housing for anyone with a positive COVID-19 test, facilitating the development of a small business resiliency fund – with priority given to women and minority owned businesses – and other services.

To help create a more diverse stock of housing options, Lempert looks to the increase of affordable housing recently approved and partially funded by Princeton. The allocation of funds in the municipal budget also plays a role in various agencies abilities to respond to the needs of the community. Retirements and restructuring of some departments help adjust the budgets annually.

One department budget that is receiving a closer look due to recent protests is the police. At the time of consolidation in 2013, combining the township and the borough’s police departments into one helped guide reductions in spending. Each year the numbers are analyzed, and already a 3-4% reduction was put in place from last year to this year for the police.

“Looking at a budget and saying maybe we don’t need 6 cars this year, instead we can pay for a 2nd responder. That’s program budgeting,” states Princeton Police Chief Nick Sutter. “Let’s not conflate that with defund the police.”

“Looking at a budget and saying maybe we don’t need 6 cars this year, instead we can pay for a 2nd responder. That’s program budgeting,” states Princeton Police Chief Nick Sutter. “Let’s not conflate that with defund the police.”

Sutter has been in the department for 25 years, at the helm for the past seven. He says he’s been pushing for five years to have a better system of 2nd responders, those that follow up after a situation has been de-escalated to find proper assistance for the person in need.

“In my experience it’s become a revolving door – we don’t solve the problem. We deal with it in the moment, make it safe and often respond back to same person again. We need a crisis intervention team,” Sutter adds. “I don’t know a social worker that’d walk into an unsecure scene that’s violent. That’s unrealistic.”

The police have developed a strong relationship with Corner House for those with drug dependency issues, but more help is needed with situations such as homelessness and personal crisis. That would fall to 2nd responders. Lempert says with today’s increased support, perhaps now is the time they’ll find more funding for them. To have a responder like a social worker first on the scene, as suggested by supporters of the “Defund the Police” movement is less likely. While Lempert, Sutter and others agree it would be wonderful to have a team of mental health professionals available 24/7 to respond with the police, in a municipality like Princeton, the budget capabilities are not there. Head of Human Services, Melissa Urias, whose only other staffer is a part-time administrative assistant, says resources severely limit follow-up and intervention capabilities.

“Throughout the nation, mental health and social services are under-resourced. Unfortunately, here in Princeton, it is no different. Police officers are meant to act as guardians of public safety but are often the first to respond to individuals dealing with complex issues,” Urias explains.

The police often refer people to Human Services or reach out directly after a situation. To better address the needs of those in the Black community, Urias says she is meeting with other leaders and partners to be sure to understand their needs and focus on desired improvements. Sutter admits his department can always do better but states it has included the community in its planning process and policy decisions for years.

Loretta T. lives nearby and her children attend Princeton Public Schools. She agrees that community-oriented policing is a must. “When law enforcement presence goes beyond emergencies, police officers and communities are able to truly connect with one another and therefore view each other as whole individuals rather than the narrative be pushed by the media. It invites an opportunity to have authentic experiences which shape broader perceptions.”

Loretta T. lives nearby and her children attend Princeton Public Schools. She agrees that community-oriented policing is a must. “When law enforcement presence goes beyond emergencies, police officers and communities are able to truly connect with one another and therefore view each other as whole individuals rather than the narrative be pushed by the media. It invites an opportunity to have authentic experiences which shape broader perceptions.”

The national narrative has caused the department to take another look at its failures and look at how it can improve. Recruitment, policy, supervision and training – all guided by community input, are constantly evaluated. 4-5 retirements are expected this year, including that of Chief Sutter, but the 55-person department has made an effort to reflect the community in its hiring. As of the latest reports from 2019, the Princeton Police Department has hired more people of color than are represented amongst its residents:

Racial Demographics of Princeton Police Department

| Percentage | ||||

| Caucasian | 73% | |||

| African American | 8% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 16% | |||

| Asian | 4% | |||

As for policy, Princeton police say they are listening, but have been proactive too. The policy towards immigration and law enforcement, for example, was put in place with locals back in 2013, before it became a national issue. Redefining Use of Force, Vehicle Pursuit and Forcible Stopping was officially done in 2017 but all have been highlighted through the department’s training for at least seven years. Now, Sutter and his team are looking to see if they can get stricter in some areas than what the state mandates. In terms of training his officers, he believes their focus has often stemmed from national community needs and instead they should add more training based on local community experiences. Improvements can also be made in vetting out unconscious biases and training officers to better recognize and deal with theirs.

The Town Council resolution aiming to dismantle racism, applies to all municipal departments, not just the police. Each is being asked to take a closer look. As soon as town council approves a framework recommendation from the Civil Rights Commission, Lempert claims it will have the tools to better review ordinances and other needs through a racial equity lens.

“I think having a framework will be helpful and almost essential to get us to move from conversation into action,” declares Lempert. “It’s important we take this opportunity and we look at ourselves and our institutions with open eyes, and we use this period where everything is being shaken up already – no one has ever lived through a period like this before – and when we come out of it we don’t just return to February 2020.”

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!