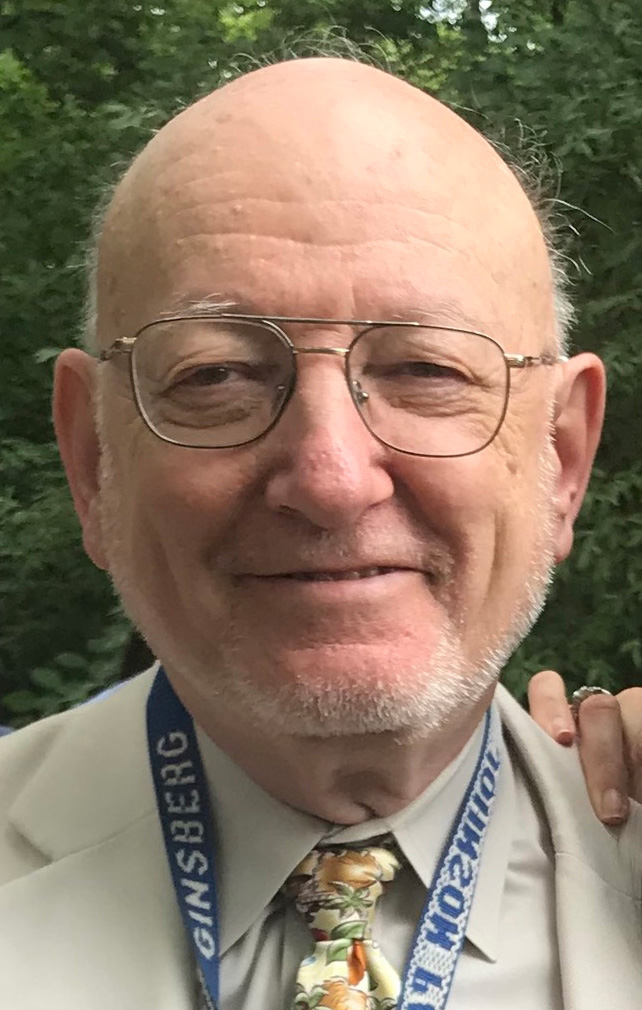

Our Editor’s Conversation with Dr. Robert Ginsberg, Principal at Johnson Park Elementary School

The anticipation and realization of COVID-19 in first the U.S, and later in Princeton, has been unbelievable and overwhelming for many. There was little expectation that we’d have to change the way we spend our days, the way we socialize and the way we teach. Dr. Robert Ginsberg, Johnson Park Elementary School’s Principal for the past 21 years, shares with us what it’s like from the inside. He has worked in education for 56 years, and as an administrator in Princeton for 32. From his vast experience, Dr. Ginsberg provides insight on the uniqueness of our situation and how we’re all planning and adjusting to the current reality.

1. From an educator’s standpoint, how does the COVID-19 outbreak compare to other major historical moments?

We’e been out of school in the past, but never like this. We’ve never sought to prepare to provide remote learning for everyone. No one predicted we’d be out for over a week with Hurricane Sandy, and for that we didn’t have time to prepare, so that experience was quite different.

At least, for this time, we had several days to get ready and get our pupils and their parents somewhat ready for remote learning. Having said that, I should note that most of us have had little or no training on how to deal with remote learning.

We’ve learned a lot from our preparation and I’m sure we’ll learn more afterwards as we debrief with our colleagues. Regardless of the details and logistics that we’ll discuss, it’s evident that, going forward, we need to do more to take advantage of the technology we have available—and not just for emergencies that require remote learning. I expect that this experience will impel us to focus on how we can make better and more extensive use of computers and other devices to expand teaching and learning beyond the standard four walls of our classrooms, even under normal circumstances.

A second issue that this emergency has highlighted is that of equity. As we considered remote learning, we immediately recognized that the inequities in our community presented challenges.

As our district seeks to confront and address matters related to the differential achievement and success of students throughout our schools—the so-called achievement gap—we can’t, just because of an emergency, abandon our responsibility to serve all our children responsively. I’m proud that my colleagues—aides, teachers, bus drivers, administrators, school-board members—have undertaken efforts to ensure that the families of food-challenged youngsters, who usually receive subsidized meals at school, continue to receive their meals. And, those same folks have invested time, expertise, and resources to put devices in the hands of pupils who’ll need them to learn remotely.

2. Are there other major national/local moments you have been through as an educator that have affected school?

The only significant “moment” I can recall as a student was the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963, when I was a college senior. At the time, I happened to be president of my fraternity, and I wasn’t prepared to have everyone turn to me for advice about what to do; I was as shocked as they were!

During my years as an educator in Brooklyn, East Brunswick, and Princeton, I was an actor in several strikes, and on both sides of the picket line. If one puts aside issues of salaries and benefits, both of which tended to improve as a result of the strikes, the results of each situation for pupils were a mixed bag.

While some conditions improved—when I started teaching, we had up to 42 kids in a class; by the time I left Brooklyn, the limit was down to about 30—we were never able to make up the instructional time our kids lost. Even when “settlements” called for adding hours to schooldays to make up for lost time, our schooldays were too long for the extra hours to be effective for instruction or learning.

Superstorm Sandy was a unique occurrence, because it didn’t allow us time to prepare, and being out of school for over a week was a challenge for educators and parents alike. At that time, we weren’t able to prepare for remote learning; nor did we expect that we’d have to.

Snow days, from my perspective, typically haven’t had major effects on school because, with at least a handful each year, we’ve become accustomed to dealing with them. The only exception to that was two years ago, when, after two days out for a huge snowstorm, all our schools, except Johnson Park (JP), were open.

Because we still had no power at JP, we had our youngsters report to school, gather their learning materials, and then, for the day, we transported them to Riverside Elementary (Pre-K’s), John Witherspoon Middle School (grs. K-2), and Princeton High School (grs. 3-5). The operation worked well because everyone—JP staff members, our colleagues at the other schools, and our district officials—worked as a team. That cooperation was obviously the key, and it will likely be the major factor in helping us surmount our current challenges.

3. In the past several weeks, how was the school acting differently in sanitation protocol compared to that of major flu outbreaks?

Our schools have put in place cleaning protocols that go beyond our typical daily practices and even beyond what we’ve done during the flu season. Our custodial colleagues have wiped down surfaces, handrails, doorknobs, and so forth in our common areas; our teachers have wiped down our boys’ and girls’ desktops and other classroom surfaces. At night, our custodians have revisited those surface cleanings.

Beyond what we’ve done during flu season—although I’d guess some of these procedures will become more common during those outbreaks in the future—our tech coordinators have regularly cleaned all our computer keyboards. Our bus drivers have, twice daily, thoroughly cleaned our buses and the surfaces within them.

4. You have a very international community at Johnson Park. Have you had to ask any families returning from abroad to self-quarantine?

Yes, we had two families who self-quarantined. Each did so willingly and voluntarily. Both, having come from areas where officials had locked their communities down, already knew how quickly the virus could spread and how devastating the virus’s effects could be.

5. Princeton Public Schools announced the decision to go to remote learning Thursday night. What goes into a decision like this?

Closing a school isn’t a simple decision. A schools’ superintendent has to consider a range of factors that include, among other factors, adhering to State regulations.

For Sandy, the State required school systems to make up all the days they closed. In this crisis, for the first time ever, the State has allowed schools to submit plans for counting students’ participation in remote-learning options as acceptable for “school attendance.” Two weeks ago, that wasn’t possible; now, it is.

Superintendents must also consider childcare challenges. Who’ll watch our youngsters if their parents aren’t home? Who’ll provide their meals if our schools aren’t?

Sometimes, as in our current situation, individual parents “voted” by deciding to keep their children home. Of course, we should recognize that many of our families didn’t have the privileged circumstances that would allow them to make such a call.

So, calling for a school closing isn’t so simple as many believe. And, of course, particularly with regard to snow days, there are always lots of folks, who don’t have to consider all these factors, ready to second-guess their district’s leader.

6. Were families already keeping children home?

By Fri., Mar. 13th, our last day before we closed our schools, parents kept home over a third of our children.

7. I’d imagine this is a logistical nightmare for an administrator. How did you organize?

One of the lessons we learned from previous emergencies, such as the time we had to evacuate all our learners to RS, JW, and PHS, was that teamwork is essential. And we’ve put that lesson into operation for this crisis.

Early on, Steve Cochrane, our superintendent, formed a leadership team—a task force, including municipal health officials, district and school administrators and supervisors, teachers, and community representatives—to consider ranges of options that might arise, including the possible need to close our schools for an extended time. Then, all our administrators, supervisors, teachers, instructional assistants, custodians, and bus drivers collaborated on specific plans and relevant logistics.

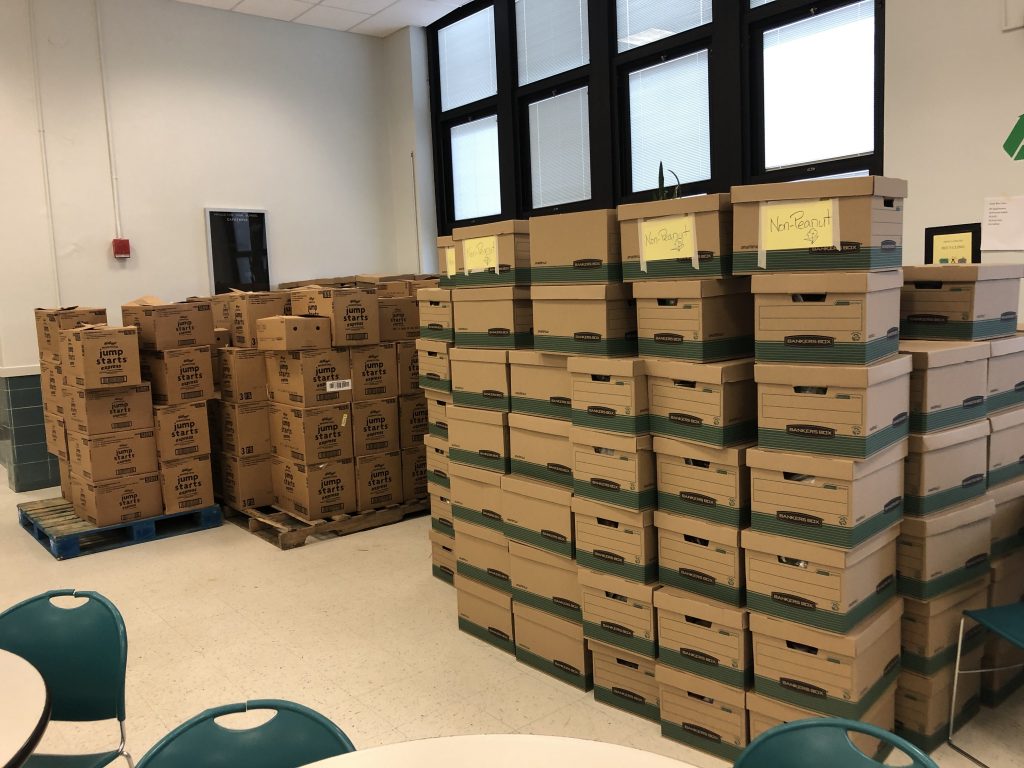

An example of one such effort has been the collegial work among our transportation-department colleagues and our aides to ensure our children eligible for subsidized meals receive them. Our transportation supervisor, Donna Bradin, laid out a series of drop-off sites for food distribution and assigned bus drivers to follow those routes.

Meanwhile, Eric Karch and Ashante Thompson, the leaders of PRESSA, the association that represents our aides, custodians, and secretaries, organized cadres of their members to ride the buses to all the sites so they could assist with meal distribution. They assigned other of their members to be present in the gym of each school to receive citizens’ donations of food.

Ms. Bradin’s, Mr. Karch’s, and Ms. Thompson’s efforts, and their colleagues’ enthusiastic support, enabled many of the rest of us to focus on providing remote instruction for our students. Administrators’ and teachers’ initiatives with regard to delivering instruction would have been less successful if those other members of our district’s team hadn’t stepped in and given us the space and time to address our youngsters’ learning.

8. How can you teach elementary students, especially K-2, virtually?

Anyone who suggests that virtual instruction will be easy for our teachers or our pupils is incorrect. One of the essential pillars of good teaching for younger children rests on the relationships between teachers and kids; computers can’t replace our teachers’ warmth, caring, humor, and empathy.

Having said that, we can use computers to present resources to our learners. And our teachers, working diligently and creatively, have created lessons to engage our youngsters.

Each grade level’s teachers worked in teams to fashion learning experiences that would be curriculum-related and meaningful to our children. They constructed activities that would move our boys and girls incrementally ahead to new discoveries, deeper understandings, and enhanced skills.

So as not to lose the personal touch, all our professional-staff members — teachers, child-study-team members, counselors, special-needs therapists, everyone! — have committed to reaching out several times a week to our pupils and their parents. Our colleagues will be telephoning our youngsters and e-mailing them and their parents; some may even Skype or videoconference with them.

9. Specifically, how is the remote learning planned for Johnson Park?

For grs. PK-2, our teachers developed two weeks (ten days) of learning activities that they packaged in learning packets. Our teachers sent home predominantly computer-based learning activities for the same time period for our third-through-fifth graders.

Each day’s activities have aimed for about one hour of reading, one hour of writing, one hour of math, 30 minutes of science or social studies, and 30 minutes of a “special,” such as art, music, physical education, and so forth. We’ve sought to include about four hours of schoolwork per day.

For grs. PK-2, teachers will collect our boys’ and girls’ work when our pupils return, or, if our closure lasts more than two weeks, we’ll have parents bring the work to school as they pick up additional assignments. For grs. 3-5, teachers can assess the work electronically.

10. What will happen with aides, cafeteria workers, custodians?

Our district’s aides, bus drivers, and cafeteria workers came together on Mon., Mar. 16th, our first day of remote learning, to sort, package, and load two weeks of meals for over 500 students onto our district’s school buses. Then, those staff members delivered the meals to eligible families at over a dozen sites around Princeton. In addition, some aides, who work with individual pupils, have reached out to them and shall continue to do so to ensure they understand their assignments and are confronting them successfully.

Our district’s aides, bus drivers, and cafeteria workers came together on Mon., Mar. 16th, our first day of remote learning, to sort, package, and load two weeks of meals for over 500 students onto our district’s school buses. Then, those staff members delivered the meals to eligible families at over a dozen sites around Princeton. In addition, some aides, who work with individual pupils, have reached out to them and shall continue to do so to ensure they understand their assignments and are confronting them successfully.

Meanwhile, our custodial colleagues have been thoroughly cleaning our schools so that, when our youngsters and staff members return, they’ll be in conditions that are as pristine as we could make them. When we resume schooling, we want all our stakeholders to be confident that they’re returning to safe environments.

11. They say that people over 60 should take more precautions. It’s no secret that you are 76. Do you have personal concerns working in a school at a time like this?

Initially, I had no qualms about doing so. However, my primary-care physician explained to me that people over 50, with underlying medical conditions (I have one), should remain at home; as well, people over 70, even without underlying medical conditions should also remain at home.

So, on both counts, I need to follow her recommendations. And, whenever I comment that I might do otherwise, my wife and daughter jump on my case. Do you need a definition for “relentless?”

12. Having worked with children and their parents for decades, any words of advice for them to be successful during this time at home?

Stay calm. Realize you’re helping your child because he or she needs your assistance.

Often, teaching one’s child anything is akin to teaching a teenager how to drive: It can be terribly frustrating. In the latter case, parents often contract the process out to someone else (like a driver-training school). Well, for now, parents can’t contract the process out to their children’s teachers, so parents need to summon their patience. And, if a parent senses he or she is getting annoyed, frustrated, or angry, that’s the time for everyone to take a break!

Remember that you’re seeking to help your kid because you love him or her. Don’t let a school assignment get in the way of that relationship.

Editor: Lisa Jacknow; Photo courtesy of Princeton Public Schools

Robert A. Ginsberg is currently Principal at Johnson Park Elementary School in Princeton. He has been a public-school educator since 1964 and received his Ph.D from Cornell University. In the mid-1990’s Ginsberg received the Mort Pye Award from The Star-Ledger as the outstanding educator in the Star-Ledger’s circulation area and has been honored by the Princeton Education Foundation and, last month, by Send Hunger Packing Princeton (SHuPP).