COVID-19. Delta. Omicron. The virus that just goes on and on and on has taken its toll on our community in so many ways. In an attempt to stop the spread back in March 2020, we all recall when Princeton Public Schools (PPS) and others went fully remote for the remainder of the school year. The next fall PPS remained remote until an every-other-week schedule began in-person at Princeton Middle School (PMS) in October. Some students stayed home through the end of the 2020-2021 school year due to compromised health, fear and other anxieties. Warnings were made about the effects this isolation and separation would have on children.

COVID-19. Delta. Omicron. The virus that just goes on and on and on has taken its toll on our community in so many ways. In an attempt to stop the spread back in March 2020, we all recall when Princeton Public Schools (PPS) and others went fully remote for the remainder of the school year. The next fall PPS remained remote until an every-other-week schedule began in-person at Princeton Middle School (PMS) in October. Some students stayed home through the end of the 2020-2021 school year due to compromised health, fear and other anxieties. Warnings were made about the effects this isolation and separation would have on children.

So, when the 2021-2022 school year started, remote school was not an option. Experts felt there were parameters in place to safely learn in-person. This brought more than 800 children plus teachers and staff together at the PMS building, after an academic and social experiment that was bound to start showing its fallout. And in short time it did.

BEHAVIORAL EVIDENCE

“It’s not necessarily that we’re seeing different behaviors, but we’re seeing an increase perhaps in some behaviors because students haven’t had the opportunity to shake hands and gather together, so a lot of the feelings and excitement has been contained and they’re in a space they feel comfortable expressing themselves,” stated Dr. Edwina Hawes, PMS psychologist, at a virtual parents meeting on December 9, 2021 called to address a rise in behavioral incidents at the school.

Excited interactions, some leading to injury, were the most common but there were also more serious reports of harassing behaviors, taunting and more.

“Many of the things surrounding horseplay, that’s normal middle school behavior,” explained PMS Principal Jason Burr at the same meeting. “Our students don’t always know how to say I like you, so, they slug you in the arm.”

From October through December 2021, PMS reported 10 investigations, comprised of 4 Harassment, Intimidation, Bullying (HIB) incidents and 6 other alleged offenses that didn’t fall under HIB. HIB is the policy used to cover more targeted and intentional incidents, not necessarily inclusive of a slug in the arm or some other inappropriate behaviors. As explained on the district website, HIB ensures incidents get a thorough investigation, and as the BOE policy states is “perceived as being motivated by either any actual or perceived characteristic, such as race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, or a mental, physical or sensory disability, or by any other distinguishing characteristic.”

From October through December 2021, PMS reported 10 investigations, comprised of 4 Harassment, Intimidation, Bullying (HIB) incidents and 6 other alleged offenses that didn’t fall under HIB. HIB is the policy used to cover more targeted and intentional incidents, not necessarily inclusive of a slug in the arm or some other inappropriate behaviors. As explained on the district website, HIB ensures incidents get a thorough investigation, and as the BOE policy states is “perceived as being motivated by either any actual or perceived characteristic, such as race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, or a mental, physical or sensory disability, or by any other distinguishing characteristic.”

For comparison, there have been only 1 HIB incident and 5 other offenses reported this school year amongst all five other PPS schools combined. And, if we go back to the last full “normal” year of school from 2018-2019, there were a total of 15 incidents reported the entire year at PMS (6 HIB, 9 other offenses).

It makes sense to see problem behaviors occurring more in the middle school compared to others since the pre-teen to young teen years are ripe with hormonal and physical changes, and a normal age for social experimenting. Combined with the strains of the pandemic, schools nationwide have been seeing this trend.

“The kid doing bullying is bigger, stronger, or more socially powerful, or it’s a group of kids picking on one kid. That power difference, that’s what makes it difficult or impossible for the kid being targeted to protect or defend themselves. For actual bullying, we need adults to step in and say that’s crossing the line. A lot of times, kids do bad behavior and it’s not bullying, it’s a clumsy effort to handle conflict or its poor emotion regulation skills, and that’s very different,” shares Dr. Eileen Kennedy-Moore, Princeton psychologist and author of Growing Friendships, a Kids Guide to Making and Keeping Friends. “We can certainly all see a big drop in civility of the adults, so it’s not surprising that when we adults are behaving with less than kindness that there’s less kindness among kids as well. The isolation of COVID has been very difficult on everyone.”

“The kid doing bullying is bigger, stronger, or more socially powerful, or it’s a group of kids picking on one kid. That power difference, that’s what makes it difficult or impossible for the kid being targeted to protect or defend themselves. For actual bullying, we need adults to step in and say that’s crossing the line. A lot of times, kids do bad behavior and it’s not bullying, it’s a clumsy effort to handle conflict or its poor emotion regulation skills, and that’s very different,” shares Dr. Eileen Kennedy-Moore, Princeton psychologist and author of Growing Friendships, a Kids Guide to Making and Keeping Friends. “We can certainly all see a big drop in civility of the adults, so it’s not surprising that when we adults are behaving with less than kindness that there’s less kindness among kids as well. The isolation of COVID has been very difficult on everyone.”

THE BACKSTORY

Many PMS parents were first informed about an incident at school on November 18th when Principal Burr emailed them informing that a student had been injured in the hallway. He stated that while they assessed the situation, a Shelter-in-Place had been called (this keeps learning continuous, but students are held in their same classroom or area for an extended period of time and do not enter the hallways). The school had multiple evacuations the previous week, so it wasn’t out of place to send an email explaining the Shelter-in-Place. What was different was the email included a message about the importance of being safe in the hallways and mentioned the need for students to refrain from sharing unverified information about the incident. That different verbiage sparked intrigue.

A week later, on November 23rd, Rocio Titiunik, parent of a current PMS 7th grader, sent an email to many PMS parents requesting signatures for a petition urging better intervention at PMS citing, “Many children at PMS have been victims of harassment, intimidation, bullying, violence, retaliation, and emotional distress” and claiming the November 18th incident was another in this series of events. A follow-up email from Titiunik explained she was reacting to the handling of an incident involving her daughter and a separate incident with her daughter’s friend. Parents started to talk and wonder.

What enhanced the situation further was a follow-up email sent by Principal Burr later that same day which stated, “I want to be very clear and direct: Last week’s incident was not the result of a fight, assault, or any form of violence whatsoever.”

Burr explained to Princeton Perspectives why the situation warranted multiple emails, “On the 18th, I knew what we’d concluded, but I wasn’t ready to share more details because we hadn’t at that point touched base with all the families involved.” He went on to add, “On the 18th, I wasn’t prepared in my message to discuss what I eventually discussed on the 23rd when I specifically called it an accident.”

Just after Thanksgiving, Princeton Middle School sent a survey to parents, trying to get a gauge of each student’s current experience at the school, including a question about whether their child felt safe. The circumstances of the incidents combined with the emails and survey prompted some to start wondering if things might be problematic, as Titiunik described.

“Certainly, given the news you read nationwide about how difficult it is for students to readjust to a full day of school and how they’re doing in the way they are making friends, keeping friends, all of those things, we thought it was a good time to try and get a measure of how people were feeling,” noted Burr, to explain the survey. “You want every child to feel safe at school. I think we can directly tie when a student feels safe at school, they’re more likely to do better. Safe means a lot of things, safety related to not just physical wellbeing but mental wellbeing.”

So, was the mental and social fallout of the pandemic leading to behavioral problems at PMS or was it a series of robust physical interactions gone awry? To respond to parental concern the previously referenced December 9th meeting was called with parents, to discuss the school environment, what was going on and what is being done.

So, was the mental and social fallout of the pandemic leading to behavioral problems at PMS or was it a series of robust physical interactions gone awry? To respond to parental concern the previously referenced December 9th meeting was called with parents, to discuss the school environment, what was going on and what is being done.

At the meeting, Principal Burr noted that due to the current mental health crisis and pressure on kids to resume their lives and schooling, there have been several incidents. And yes, some had crossed the line, violating the HIB policy.

“These are challenging times. The way students emote may be a little different, the way they react may be different. The behaviors we see sometimes violate our code of conduct. And we have to deal with that accordingly but also with the understanding of all they’re experiencing,” Burr explained to parents at the meeting. He further shared with Princeton Perspectives, “We have discipline in this building, and we have rules. We need to do a better job of talking about restorative practices. We need to better relay consequences.”

What are the consequences? What should they be?

“Practically, if your kid has done something less than kind, it is important to be thinking about how to get that kid back on track with being kind. They need to recognize the impact of their actions and, if possible, make amends and certainly make a plan for what they can do differently moving forward,” explains Dr. Kennedy-Moore.

ADMINISTRATIVE RESPONSE

The district says it is being intentional in dealing with each individual situation. Some, like Titiunik, weren’t feeling enough was being done in response to her daughter’s situation and her petition led to a meeting with PPS Superintendent Dr. Carole Kelley and Principal Burr. She pushed for changes including a request for schools to be more transparent and communicative in detailing events or incidents and feels she’s already seen improvements in the emails. But Titiunik also feels the specifics of incidents can affect the outcomes.

The district says it is being intentional in dealing with each individual situation. Some, like Titiunik, weren’t feeling enough was being done in response to her daughter’s situation and her petition led to a meeting with PPS Superintendent Dr. Carole Kelley and Principal Burr. She pushed for changes including a request for schools to be more transparent and communicative in detailing events or incidents and feels she’s already seen improvements in the emails. But Titiunik also feels the specifics of incidents can affect the outcomes.

“A written, verbal or physical act, or any electronic communication that results in harm, but is not motivated by a distinguishing characteristic, falls outside of the definition of HIB and is therefore not covered by the HIB policy. Of course, a non-HIB offense can still be addressed by the school as a violation of the school code of conduct, but how the school addresses it is not as tightly regulated,” expresses Titiunik. “This leaves a lot of children who are victims of non-HIB offenses unprotected, in the sense that they do not have a clear protocol that the school must follow to protect them, and they often see no resolution and no accountability.”

PMS is working to move forward in constructive ways to prevent future incidents, HIB or otherwise.

“All threats of harm to self are taken seriously and are addressed by employing district-wide procedures to ensure that students receive immediate attention and care,” shares PPS Superintendent Dr. Carole Kelley. “Meanwhile, initiatives are in place to proactively work with all students on self-awareness and self-management through lessons and school-wide initiatives.”

Both Kennedy-Moore and PPS suggest the greatest opportunity to do so is through empowering the child by building connections and community.

Some ways the middle school historically built community have been disturbed by the pandemic. For example, last school year started with no extra-curricular activities. Then they evolved and now most sports teams and after-school clubs are available. But even when offered, masks and social distancing may alter the engagement and connections. Community period is another mechanism once used that PMS hopes to revive 2nd semester.

“It’s mostly a way students connect to adults and others in the building in a non-academic way. Trying to get students to meet someone they feel connected with,” details Burr. “I have felt strongly to begin every community period with a greeting which involves a handshake. It’s thought if you have to shake someone’s hand you are less likely to take their French fries and throw them across a room or something.” Yet even a handshake is a no-no during COVID.

What is happening is that in good weather, PMS has a longer lunch block that allows the student to be outside with time to eat (safely and without a mask) and interact socially. When the weather is unfavorable, lunch block is indoors, rotating students between 3 areas. One is Social Emotional Learning (SEL). For approximately 15 minutes, teachers lead discussions on mindfulness or meditative practices, or engage the students in activities to learn healthy ways to identify and manage emotions, engage with others and make decisions.

“Spending 2 years alone in their bedrooms, staring at themselves on Zoom is not good for kids. It heightens their social anxiety, makes them more self-focused and self-judging. Exactly the opposite of what is needed for friendship, which is to be able to focus outward on ‘what can I give’. That generous outward focus and to be able to imagine other peoples’ perspectives,” explains Dr. Kennedy-Moore.

A mentorship program, linking students that are exhibiting social, emotional or academic concerns with staff members aims to use one-to-one connections to support the child. A new counseling group has also been established led by PMS school counselors to address pandemic-related stress.

Additionally, Health/Physical Education have become one of the primary core classes now offered four times weekly. This is being enhanced with the building of a new Yoga Studio for students to learn more about meditation and mindfulness, both to create openness and to ward off incidents but also as a space to think and learn about something one may have done.

PPS also wants to work collaboratively with parents to get through this transition. The December survey invited parents to become part of a Parent Focus Group. Run by PMS Asst. Principal Stephanie DiCarlo, it first met last week to identify parents’ areas of concern and will meet two more times to create an action plan of what can be done to reduce issues of concern and increase areas of positivity. In May, the group will assess how things are going and what can be done moving forward.

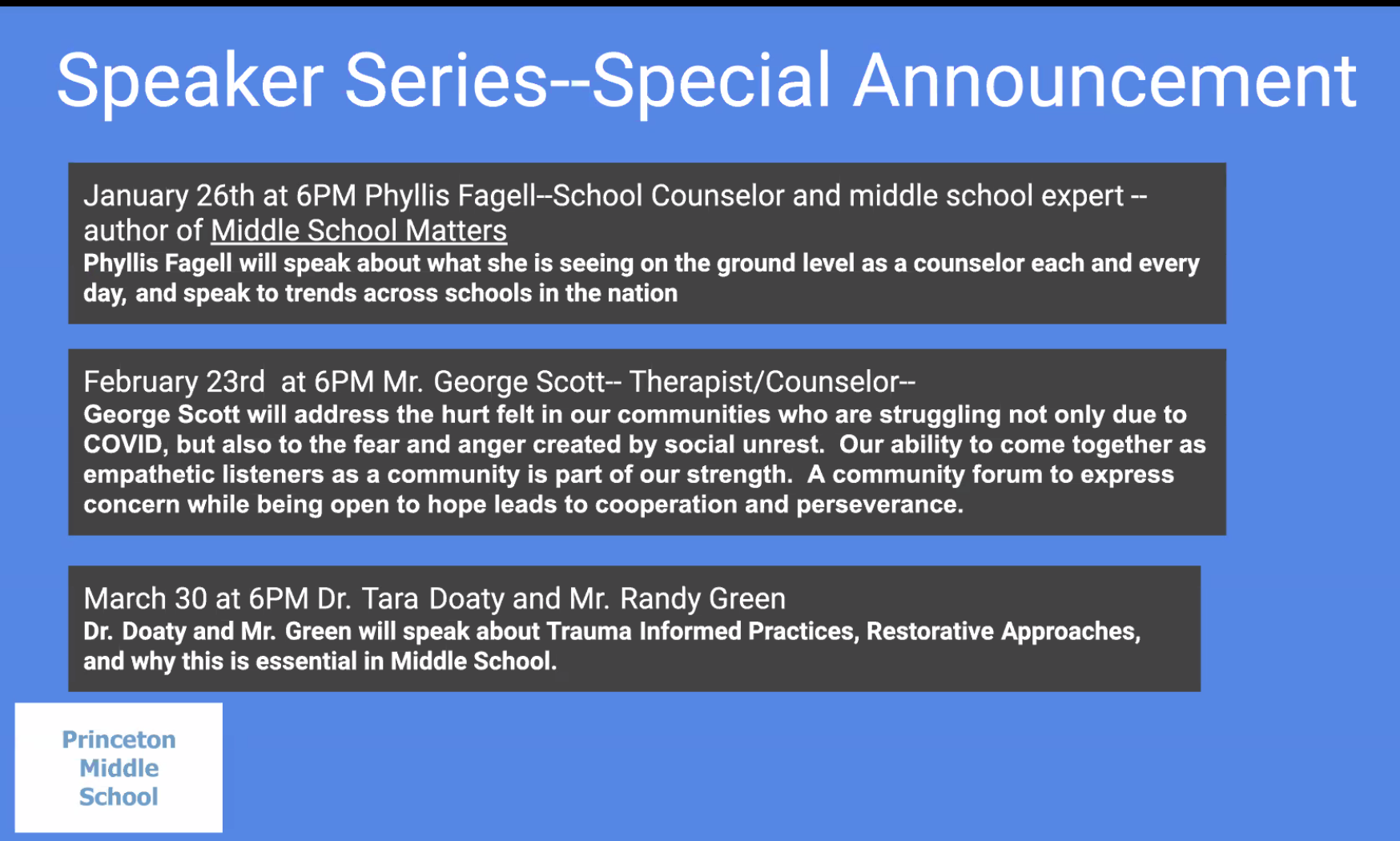

PPS has also put together a speaker series to provide insight and education to parents. To date, the schedule for Zoom speakers remains as follows:

Additionally, Understanding Brain Development and Mental Health: How Parents Can Build Resiliency and Healthy Coping Skills in Children and Adolescents led by child and adolescent psychiatrist Gal Shoval is to be held in-person on May 17th.

“I have enthusiastically supported Mr. Burr and his team in developing and expanding these programs. The middle school team works hard to integrate supports into all aspects of the middle school experience,” states Dr. Kelley.

Titiunik and other parents are appreciative of the support and that PMS has and will continue to implement ways to address the cause and effect of the incidents and to help the students through this unprecedented time.

With the rise of Omicron, some parents have requested the district return to remote learning, to keep kids safe. But as Burr pointed our earlier, safety is not just physical, it is also mental. December showed signs of students adjusting to a routine and each other. In compliance with recommendations from state and federal authorities and to continue to move forward, PPS aims to remain open, in-person to best meet the mental, educational and social needs of all students.

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!