For decades Princeton has attracted scores of visitors as well as families and retirees who seek to put down roots in this leafy, bookish town. It’s easy to see why: Princeton boasts an enviable combination of shopping vs. greenspace, village vibes vs. cultural sophistication, quaint colonial architecture vs. easy access to major highways. Of course, all of this comes at a steep price, as the white-hot real estate market currently demonstrates. But how did Princeton come to strike this delicate balance? In other words, how did Princeton become Princeton?

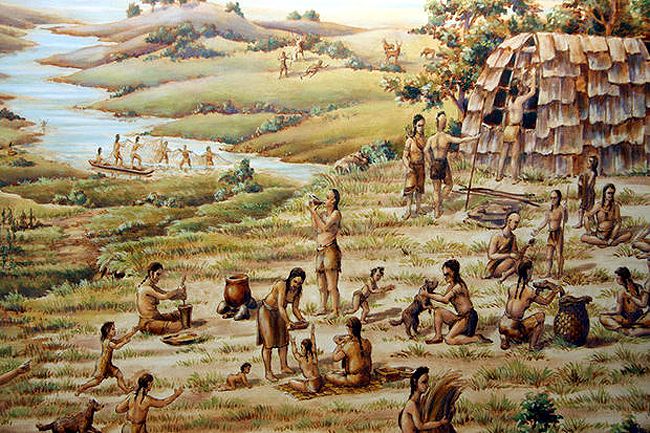

The answer to this question begins with geography. The land on which Princeton sits was inhabited by the Lenni Lenape people for thousands of years. By the eighteenth century, European settlers had arrived in this same area, including several Quaker families who built a community along the Stony Brook. At the same time, a road connecting two nascent cities, New York and Philadelphia, was developing; and “Prince-town” became a convenient way station at the midpoint along this road, known as The King’s Highway–later Nassau Street.

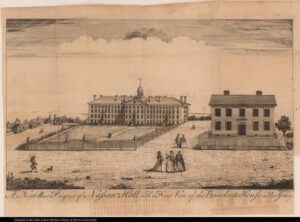

Princeton has also benefited from the establishment of not one but three important educational institutions. The first arose in 1756 when the College of New Jersey relocated to Princeton from Elizabeth. Only the fourth college to be established in the colonies, the College of New Jersey was intended to train Presbyterian ministers. Stately Nassau Hall was the very first building constructed on the campus; Maclean House–now the home of Princeton University’s Alumni Association–followed several years later. Twice gutted by fire, Nassau Hall was rebuilt both times and is still used today. In 1812, a second educational institution was established: The Princeton Theological Seminary, whose founders sought to stanch a creeping secularization at the College. Lastly, the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), a think tank, was founded in 1930; and Albert Einstein became its first faculty member, forever linking Princeton to the beloved fuzzy-haired genius.

Despite these notable institutions of higher learning, Princeton might have stayed a sleepy hamlet, were it not for the ambitions of Commodore Robert Field Stockton (1795–1866). A scion of the wealthy Stockton family, the Commodore became one of the chief investors of the Delaware and Raritan Canal, which, along with other nineteenth-century canals, transformed transportation and brought new commerce and people to the Princeton area. One of Princeton’s main arteries, Alexander Road, was originally named Canal Street and was created to expedite travel between Princeton’s heart and the newly-emerging canal wharves. Princeton’s connection to the canal–and later the railroad built alongside it–helped turn the college town into a busy hub.

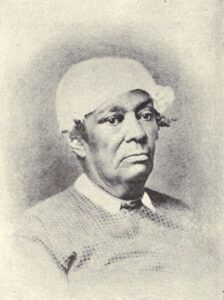

Princeton was also shaped by less well-known figures such as Betsey Stockton, an African American woman formerly enslaved by Ashbel Green, eighth president of The College of New Jersey. After being manumitted, Stockton (1798? – 1865) became an influential educator in Princeton and beyond. In Princeton she taught at the lone school for African American children for thirty years, influencing two generations of students. Stockton was also an original member of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, which still features a stained-glass window donated by her devoted students. In 2018 Princeton University created a public garden — located between Nassau Street and Firestone Library — to honor Stockton’s significant contributions to Princeton and its longstanding local African American community.

Princeton was also shaped by less well-known figures such as Betsey Stockton, an African American woman formerly enslaved by Ashbel Green, eighth president of The College of New Jersey. After being manumitted, Stockton (1798? – 1865) became an influential educator in Princeton and beyond. In Princeton she taught at the lone school for African American children for thirty years, influencing two generations of students. Stockton was also an original member of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, which still features a stained-glass window donated by her devoted students. In 2018 Princeton University created a public garden — located between Nassau Street and Firestone Library — to honor Stockton’s significant contributions to Princeton and its longstanding local African American community.

The College of New Jersey’s transformation into a world-class university has also impacted Princeton. In the nineteenth century, two remarkable presidents, John Maclean Jr. and James McCosh, worked to transform the school by raising funds, adding faculty, and improving the curriculum. In 1896 the College marked its sesquicentennial with parties, lectures, and a torchlit procession through town, the forerunner of today’s P-rade; and President McCosh’s fervent dream of building a great university was realized with the formal announcement that the College would henceforth be known as Princeton University. The building spree that then ensued –funded by the ever-generous alumnus Moses Taylor Pyne — endowed the newborn university with an array of impressive Gothic edifices, many of which were built from locally-quarried stone by Italian immigrant stonemasons and still stand today.

Princeton University’s transformation continued under the guidance of Woodrow Wilson, who served as president for eight years. Although Wilson implemented key improvements–such as the introduction of smaller classes–he actively discouraged the admission of African American students. As a result, his legacy at Princeton University has been diminished, which is reflected in the 2020 decision to drop Wilson’s name from the university’s famed school of international affairs. This complex history can be contemplated at Scudder Plaza, where a marker titled “Double Sights” was installed in 2019.

The high quality of life in Princeton has also been enhanced through the efforts of its citizens. The 1918 flu epidemic spurred residents to found the town’s first hospital (now relocated to Plainsboro) while the town’s schools, sanitation, and streets were upgraded in the early twentieth century, in part because of the crusading efforts of a women’s organization, the Village Improvement Society. Princeton’s star rose higher as it became a business and research nexus in the post-World War II era, when a variety of institutions and corporations sought local space and talent, including the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, the Sarnoff Corporation, Johnson & Johnson — to name a few. As a growing population compelled the conversion of farmland into housing developments, a preservation movement helmed by concerned residents sprang up to protect open space within the town’s borders.

Today Princeton remains more popular than ever as both a tourist destination and a place to live. This popularity comes with a cost, as the eternal arguments over parking, development, and density demonstrate. Plans for affordable housing and an expanding university campus have often been met with dismay. But the town’s government and anchor institutions, especially Princeton University, as well as engaged citizens will continue to discuss, debate, and compromise. This is the key to ensuring that Princeton becomes the best possible Princeton: a diverse, welcoming, economically vital, and livable community.

Today Princeton remains more popular than ever as both a tourist destination and a place to live. This popularity comes with a cost, as the eternal arguments over parking, development, and density demonstrate. Plans for affordable housing and an expanding university campus have often been met with dismay. But the town’s government and anchor institutions, especially Princeton University, as well as engaged citizens will continue to discuss, debate, and compromise. This is the key to ensuring that Princeton becomes the best possible Princeton: a diverse, welcoming, economically vital, and livable community.