The week of July 4th, firework displays in Lawrenceville, Hamilton, and Mercer County Park entertained us locally. Chances are as you drove to your destination, you passed obelisks and monuments on the sides of the road that you’ve passed a thousand times, but never really took time to discover what historic events they commemorate. And as the fireworks burst in celebration of the independence of our United States, you were likely more focused on who you were with and who brought the desserts than on what took place in history to allow you to gather together at all.

The week of July 4th, firework displays in Lawrenceville, Hamilton, and Mercer County Park entertained us locally. Chances are as you drove to your destination, you passed obelisks and monuments on the sides of the road that you’ve passed a thousand times, but never really took time to discover what historic events they commemorate. And as the fireworks burst in celebration of the independence of our United States, you were likely more focused on who you were with and who brought the desserts than on what took place in history to allow you to gather together at all.

The marking of Independence Day is of major significance, for in July 1776 our forefathers declared the original 13 colonies independent from British sovereignty. But that alone did not lead us to freedom, as the crown did not accept this decree. Fighting continued and six months later, about to give up at the end of 1776, George Washington and his troops instead fought on.

“After numerous defeats at the hands of the British throughout New York, turning into a dire retreat through New Jersey and across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania, the Continental Army was on the verge of collapse due to illness, desertion, poor morale, and ending enlistments,” shares Michael Russell, Princeton Battlefield Society President. “The confidence and leadership of George Washington, in the face of every possible man-made and natural obstacle, rallied his men to not only go on the offensive and take Trenton from the Hessians and then stand toe-to-toe with the British at Assunpink Creek, but also gave them the fortitude and willingness to reenlist and continue fighting for the burgeoning freedom of the new thirteen states.”

According to a 1777 diary found from militiaman Ephraim Anderson the troops marched from Mill Hill to the brook to take the Quaker road to get from Trenton to Princeton. This path took them to what became known as the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. A battle that, in conjunction with the two Trenton battles just before it, turned the revolution in our favor.

“Strategically, winning in Princeton secured New Jersey in the hands of the Americans and denied the British the ability to ever regain a foothold in the state throughout the war. The British had to change their entire approach to the war after the Americans left Princeton for the higher ground of Morristown and the Watchung Mountains,” notes Russell.

Though not as prominent as the victories at Saratoga and Williamsburg, the Battle of Princeton remains an historically pivotal moment that kept us battling for freedom. To connect us to our past and remind us to embrace our future, those obelisks, monuments and other signage you may have blindly driven by have been strategically placed all around our town and county to ensure we know of the risks and efforts that were taken in these battles nearly 250 years ago.

“Many towns and locations find an immense amount of pride in detailing the historic events which occurred in their town, county, etc. These can range from events of some historic importance (i.e., skirmishes, meetings, etc.) to the mundane (Washington’s spring outside of the battlefield – Washington’s troops stopped to drink here). These markers commemorate historic moments no matter how small,” explains Will Krakower, Resource Interpretive Specialist for The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Parks and Forestry. “The ground we walk every day, every walk in the park, every stroll down Nassau, every drive to work, rests on ground which our ancestors walked, and in some cases fought and died, for their right to live a good life – a free life.”

“Many towns and locations find an immense amount of pride in detailing the historic events which occurred in their town, county, etc. These can range from events of some historic importance (i.e., skirmishes, meetings, etc.) to the mundane (Washington’s spring outside of the battlefield – Washington’s troops stopped to drink here). These markers commemorate historic moments no matter how small,” explains Will Krakower, Resource Interpretive Specialist for The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Parks and Forestry. “The ground we walk every day, every walk in the park, every stroll down Nassau, every drive to work, rests on ground which our ancestors walked, and in some cases fought and died, for their right to live a good life – a free life.”

To mark this freedom and the 18-mile route the troops took to the Princeton Battlefield from Trenton, obelisks were placed in 1914 by the Sons of the Revolution. They used a collection of diaries, including that of Anderson’s, to map out the approximate route.

To mark this freedom and the 18-mile route the troops took to the Princeton Battlefield from Trenton, obelisks were placed in 1914 by the Sons of the Revolution. They used a collection of diaries, including that of Anderson’s, to map out the approximate route.

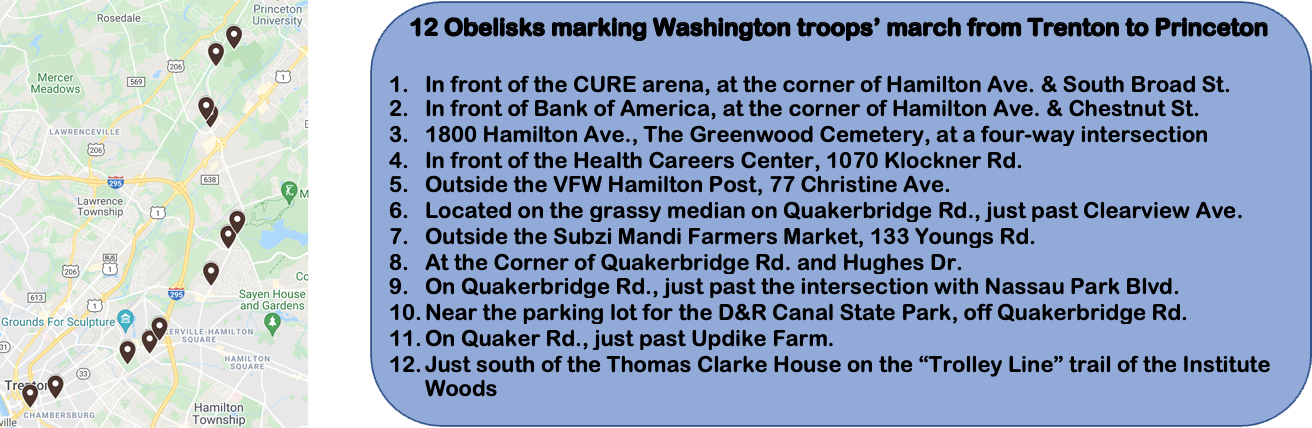

If you’re up for a fun scavenger hunt of sorts, you could set out this summer to march in the steps of the soldiers and find all twelve obelisks marking the Trenton-Princeton route:

“Keeping in mind there weren’t really roads back in 1777 along that route as we know what roads are today. Essentially, they were cutting through a lot of farmland,” details Roger Williams, historian for the NJ Society of the Sons of the American Revolution and co-founder of tencrucialdays.org. “They’re placed in weird places, in the middle of things. If you draw a straight line from the ones that are on Hamilton Avenue down through to the ones in front of Steinert High School and through the VFW post and all the way to the one on Quakerbridge Road, that gives you what we think the route was.”

In fact, Williams contends the obelisk at Quakerbridge Road and Nassau Park Boulevard was placed on the median rather than in the middle of what was then an adjacent farm field, where the troops actually marched, to ensure people would see it.

In fact, Williams contends the obelisk at Quakerbridge Road and Nassau Park Boulevard was placed on the median rather than in the middle of what was then an adjacent farm field, where the troops actually marched, to ensure people would see it.

“The troops marched through what is now Home Depot, through Home Goods and through Dicks Sporting Goods,” he explains. Williams is in discussions to move the obelisk to correctly stand in the path of the march, in front of Dicks Sporting Goods.

Back in 1777, as the soldiers made their way beyond what is now the Institute Woods, they found themselves on a farm we today call the Princeton Battlefield, which became host to the infamous Battle of Princeton. Though so much surrounding the area is different today, there are three structures in Princeton that stand to connect us to that battle.

“The Thomas Clarke House and Mercer Oak are symbolically used to represent the Battle of Princeton,” Russell explains. “The Thomas Clarke House is the only remaining structure to eyewitness the battle and characterizes the peaceful Quaker farmland that was shattered by conflict and violence on January 3, 1777. The Mercer Oak embodies the life and sacrifice of General Hugh Mercer who was critically wounded and fell on the field, dying nine days later in the Thomas Clarke House.”

“The Thomas Clarke House and Mercer Oak are symbolically used to represent the Battle of Princeton,” Russell explains. “The Thomas Clarke House is the only remaining structure to eyewitness the battle and characterizes the peaceful Quaker farmland that was shattered by conflict and violence on January 3, 1777. The Mercer Oak embodies the life and sacrifice of General Hugh Mercer who was critically wounded and fell on the field, dying nine days later in the Thomas Clarke House.”

After fighting on this battlefield, the troops made their way north and continued fighting in front of Nassau Hall. If you look closely, you can see marks on the building today, scars from the battle. (If you can find where Nassau Hall was struck, send your pictures to our Editor!).

The Princeton area is also home to many other markers and monuments to the Revolutionary War, including as the site of the first of 13 markers to the battle march that Russell previously mentioned from Princeton to higher ground in Morristown. In front of Aaron Burr Hall at Nassau Street and Washington Road you can find the first, from which the troops continued north into Kingston, marked at the Kingston Presbyterian Church Cemetery at Main and Church Streets. Nearby, there is a third marker in Griggstown at Canal Road near Copper Mine Road. And as the march continued through Somerville, Bedminster, Bernardsville, Basking Ridge, Harding Township and onto Morris Township, the other markers make note.

The Princeton area is also home to many other markers and monuments to the Revolutionary War, including as the site of the first of 13 markers to the battle march that Russell previously mentioned from Princeton to higher ground in Morristown. In front of Aaron Burr Hall at Nassau Street and Washington Road you can find the first, from which the troops continued north into Kingston, marked at the Kingston Presbyterian Church Cemetery at Main and Church Streets. Nearby, there is a third marker in Griggstown at Canal Road near Copper Mine Road. And as the march continued through Somerville, Bedminster, Bernardsville, Basking Ridge, Harding Township and onto Morris Township, the other markers make note.

The decision not to march to New Brunswick but instead to march to Morristown was actually made in Kingston, as the troops were moving north from Princeton. Historians think of this moment as the end of the Battle of Princeton, and it is commemorated with a marker there.

“On the northern bank of the Millstone River, Washington and his commanders had a council-of-war on horseback,” shares Williams. “These guys were getting out of town as fast as they could before the British could catch up with them, and they made the decision there.”

Mercer County is actually ranked as 11th of the top 15 counties in America with the most historic markers. If you want to find out where they all are, you can look online at sites like Revolutionary War New Jersey or The Historical Marker Database. If you are nearby the Princeton Battlefield, you can cross Mercer Street and make your way towards the historic columns at the back of the field. Walk just past them and to the right, you will see on the ground another marker, this one a memorial to 36 soldiers that died at the Battle of Princeton.

Mercer County is actually ranked as 11th of the top 15 counties in America with the most historic markers. If you want to find out where they all are, you can look online at sites like Revolutionary War New Jersey or The Historical Marker Database. If you are nearby the Princeton Battlefield, you can cross Mercer Street and make your way towards the historic columns at the back of the field. Walk just past them and to the right, you will see on the ground another marker, this one a memorial to 36 soldiers that died at the Battle of Princeton.

If you leave that area and continue towards what is today the former Princeton Boro municipal building, it’s hard to miss the large Princeton Battle Monument depicting Washington leading his troops that was put there in 1922. Several yards away are also several smaller markers commemorating the revolution, and people like Colonel John Haslet, a commander from Delaware that was killed at the Battle of Princeton.

If you leave that area and continue towards what is today the former Princeton Boro municipal building, it’s hard to miss the large Princeton Battle Monument depicting Washington leading his troops that was put there in 1922. Several yards away are also several smaller markers commemorating the revolution, and people like Colonel John Haslet, a commander from Delaware that was killed at the Battle of Princeton.

The Revolutionary War lasted until 1783, and Princeton would continue to be a thoroughfare for passage, as a major hospital area and with many supplies manufactured nearby in Trenton. In fact, Washington’s travels back south in 1781 are commemorated with a marker placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1981 as part of the Washington-Rochambeau Trail.

The Revolutionary War lasted until 1783, and Princeton would continue to be a thoroughfare for passage, as a major hospital area and with many supplies manufactured nearby in Trenton. In fact, Washington’s travels back south in 1781 are commemorated with a marker placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1981 as part of the Washington-Rochambeau Trail.

“In 1781, when the French and Americans marched to Yorktown, they converged at Princeton,” recollects Williams. “The French marched south on Rt. 206 from Somerville and the Americans marched south on Rt. 27 and they actually met in late August at Princeton. They encamped on what is today grounds of Trinity Church and Morven. You had 7,000 troops who just camped there for 2 nights before they headed further south.”

Two years later, Washington would return one final time to Kingston, to a home that is now located at Rockingham State Historic Site. In August 1783, he was called back to Princeton and leased this home nearby for 2 ½ months. It was there he wrote his farewell orders, officially retiring from military service at the end of October, just before the Treaty of Paris was signed and ended the Revolutionary War.

In 2026, the 250th Semiquincentennial will be celebrated honoring the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It’s planning comes at a time when much is being questioned about civil rights and the founding of our country. But the history of grit and resilience teaches us where we came from, and the buildings and markers help to ensure that we know what took place, to interpret how we wish.

“Through the lens of the 18th century citizen and soldier, the conditions of life and warfare were very different from what we deal with today. The obelisks and monuments help us consider the commitments and beliefs of our ancestors, all from a present-day perspective,” explains Russell.

If you are interested in learning more about the history and the markers in our area, you can learn more about car and bus tours here or to get a tour at Princeton Battlefield click here.

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!

Ingredients:

Ingredients: Ingredients (4-5 servings)

Ingredients (4-5 servings)

Ingredients:

Ingredients: