In Princeton, we are lucky to be able to stand in front of the home where Albert Einstein spent his final years, touch the gravestone of Aaron Burr or walk along the battlefield where soldiers fought during the Revolutionary War. Now imagine if Albert Einstein had Tweeted out his Theory of Relativity, if Aaron Burr shared the infamous duel on Facebook Live or if George Washington posted his troops on SnapChat preparing to attack the British? My, how history may have been affected.

In Princeton, we are lucky to be able to stand in front of the home where Albert Einstein spent his final years, touch the gravestone of Aaron Burr or walk along the battlefield where soldiers fought during the Revolutionary War. Now imagine if Albert Einstein had Tweeted out his Theory of Relativity, if Aaron Burr shared the infamous duel on Facebook Live or if George Washington posted his troops on SnapChat preparing to attack the British? My, how history may have been affected.

While there is so much here for us to touch and see, when it comes to learning, teaching and sharing it, technology is a tool that opens up opportunities in terms of who you can reach, how you can reach them and what you can share. This can be both an amazing tool for studying history, or a cautionary means to reshape it.

We shared with you in our January article Expanding Your Potential about the growing selection of online courses being offered. Princeton University Professor Jeremy Adelman not only took his world and global history class online but took the opportunities technology offers to take it one step further. His class has been taught online via EdX for several years now and he recently partnered with the University of Geneva and UNHCR, so his “classroom” takes place in Princeton, Geneva and at refugee camps in Kenya and Jordan all at the same time.

“They are fully integrated. They want to learn. They also have a LOT to teach us about globalization and its complexities,” Professor Adelman offers, with regards to his students in Kenya.

Adelman is often amazed by how many people he can reach thanks to technology, and the worldwide interest in the historic lessons he teaches. It invites such varied people to the table.

“Part of what we learn together is how to talk across our differences. But that is a challenge compared to the relatively homogeneous world of the walled classroom. When you introduce the world’s fractures into a course, they are more evident – and you have to explain them,” Adelman contends.

While it certainly is more challenging to teach to a variety of groups at once, taking that trip back in time together and sharing the different perspectives about it can certainly enhance any lesson.

Local historic organizations, such as Historical Society of Princeton (HSP), had relied on in-person gatherings to share most of its information, though digital and virtual opportunities were evolving. Physical photographs, diaries and collections of historic items have allowed them to inform us about important people and moments from the past. Imagine if those photographs had been taken with digital cameras or if the diaries had been kept online? The knowledge would’ve spread sooner and it’d all be so much easier to share. In 2021, digitizing and online usage has become more commonplace (in fact, more than 500 images of manuscript collections have been added to the HSP digital database this past year) and thanks to more recent technology like Zoom, HSP is now host to worldwide gatherings for learning as well.

“COVID really provided us the push we needed to dive in,” shares Izzy Kasdin, Executive Director of HSP, whose organization this year compiled its virtual history-related information and activities into what it called ‘History @ Home’. “What we’ve seen is that we’ve been able to reach more people in more places than ever before. We’ve been able to welcome scholars from across the country as speakers. People who grew up in Princeton or once lived in Princeton and moved away have reached out to us to say that our virtual programs have provided them with a way to stay connected to their former home.”

“COVID really provided us the push we needed to dive in,” shares Izzy Kasdin, Executive Director of HSP, whose organization this year compiled its virtual history-related information and activities into what it called ‘History @ Home’. “What we’ve seen is that we’ve been able to reach more people in more places than ever before. We’ve been able to welcome scholars from across the country as speakers. People who grew up in Princeton or once lived in Princeton and moved away have reached out to us to say that our virtual programs have provided them with a way to stay connected to their former home.”

Like HSP, Morven Museum & Garden, the historic home to Declaration of Independence signer Richard Stockton, worked by bringing people on-site to share its stories of Stockton, former governors who called it home and more. Learning to use technology this past year to get through the pandemic will now allow Morven to invite the world to join as it plans to celebrate the historic signing.

“As we look forward to the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, we know the eyes of the country will be looking for rich and interesting content and as a home of a signer, the only one open to the public in New Jersey, we will be ready to serve,” explains Jill Barry, Morven Museum & Garden Executive Director.

“As we look forward to the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, we know the eyes of the country will be looking for rich and interesting content and as a home of a signer, the only one open to the public in New Jersey, we will be ready to serve,” explains Jill Barry, Morven Museum & Garden Executive Director.

Beyond learning through a course or museum, many people gather global facts and historical information on their own, through the media and the internet. But be advised to ensure your source is a reliable one.

“The internet is a fantastic place for doing research and keeping apprised of the latest developments in world news. However, it’s also easier than ever to get duped by illegitimate news sources, and spread panic by sharing an article that might not even be true,” StandWithUs advises, in its Guide to Fact Checking. They also suggest checking that at least two other reputable sources are reporting similar information.

This advice also applies to Social Media. YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and more can be used as a positive means to educate people about history and share an historical-moment in-the-making. These technological advances are the way many of today’s younger generation get their information. On platforms where people tend to only read posts from the people they follow, one might only see content reaffirmed by other similar-minded followers. Here, too, it is important to not share or repost before fact-checking. Take the recent Israeli-Palestinian conflict, for example. The history of this situation is very complex and often difficult for a teenager to grasp simply via social media.

“It doesn’t lend itself to a meme or a 5 second video, or however many characters you’re allowed on Twitter,” explains Susan Heller Pinto, Senior Director International Affairs & Director Middle Eastern Affairs of ADL (Anti-Defamation League). “You really need to delve in deep. So, when you get a picture and that’s supposed to capture the entire complexity going back 80 or more years, you’re going to be found wanting and will have a very shallow impression or understanding of this very deep-rooted conflict.”

This doesn’t mean one shouldn’t get any information this way. Social Media and other platforms like Clubhouse offer first-hand perspectives, something previously not available. You just have to ensure you get the full story.

“I have teenagers, I know they get a lot of their news from TikTok and Instragram, so it’s a real challenge to give insight through these important mediums but then encourage them to delve deeper,” notes Heller Pinto. “Our historical records are based on longer documentation, and we can’t throw that away. But what appears on social media is also a representation of morays and attitudes, and that needs to be incorporated. Are you going to write the history of the Trump presidency without the Tweets? No. But you can’t go by just those.”

Today’s technology also provides a chance to respond and try to shed more light on a topic. To prevent the perpetuation of antisemitism and false information about the history of Israel, Hayden Masia, a recent graduate from Princeton Day School, found herself having to clarify mistruths being posted by schoolmates on Instagram.

“I spend more time than I’d care to admit staring at my phone screen, and more and more I see terrifying things staring back at me, people promoting false conspiracies,” Masia admits. “I find myself trying to stand up to millions of people through a tiny screen. I dip into my Notes apps, using pre-written defense mechanisms to try to make my peers understand why what they are saying is so damaging.”

It’s a big task for teenagers to try and guide such misinformation. Experts also find it their duty when those with bigger platforms, like celebrities and famous journalists post historical information that requires corrections.

“Historians have a special expertise, a special knowledge about our past and there are a lot of mistruths being spun about that both on the popular media and in social media, and we have a duty to step in and correct things,” said Princeton University History Professor Kevin Kruse in a 2019 interview on CPSAN. But, he added, there are ways to use the same technology to ensure trustworthy information is also put out there. “When I see the President, another politician or a cable host or cable guest make a misstatement about the American past, which I know well, I can offer a correction on Twitter, one which is read not just by the people that follow me but hopefully can be spread by some of the journalists who follow me and serve as a corrective to that.”

“Historians have a special expertise, a special knowledge about our past and there are a lot of mistruths being spun about that both on the popular media and in social media, and we have a duty to step in and correct things,” said Princeton University History Professor Kevin Kruse in a 2019 interview on CPSAN. But, he added, there are ways to use the same technology to ensure trustworthy information is also put out there. “When I see the President, another politician or a cable host or cable guest make a misstatement about the American past, which I know well, I can offer a correction on Twitter, one which is read not just by the people that follow me but hopefully can be spread by some of the journalists who follow me and serve as a corrective to that.”

Social media can also be used to determine what becomes historically important and how it will be interpreted. It used to be that an event would happen, it was encapsulated in time and lived on with those memories and interpretations. As Christian Zilles shared in the 2020 SocialMedia HQ article How Social Media Impacts the Way We Interpret Historical Events, social media does influence what we know, recall and share.

“The reality is that, even if an event is really a ‘non-event,’ it can generate tremendous visibility and influence within society if it is talked about, promoted, and debated on social media,” wrote Zilles.

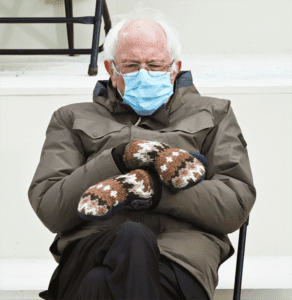

A perfect example of this is Bernie Sanders in his mittens at the Biden inauguration in January. It became a viral meme and will forever be remembered as part of that event. Is there a detail like that you can recall from any past inauguration, and would it have become such a moment had it not been recorded and shared on social media?

A perfect example of this is Bernie Sanders in his mittens at the Biden inauguration in January. It became a viral meme and will forever be remembered as part of that event. Is there a detail like that you can recall from any past inauguration, and would it have become such a moment had it not been recorded and shared on social media?

Zilles went on to explain how the historical lens events would one day be viewed from are instead immediately shaped from these platforms, adding “The filter of social media forces us to look at historical events and interpret them in real-time.”

Case in point are the posts you’ve seen this week of history-in-the-making from Cuba where social media was used to organize unprecedented protests against the regime. And as a communist country, it also had never been possible to witness public dissent in real time like we can now.

With such technology being relatively new (in terms of history) we are learning each day what benefits and consequences it brings. Rather than piecing together remnants of an old paper map, will the digitization of today help preserve information for the future? Perhaps history will be more precise when visual recordings on YouTube rather than memories document the moments. Or will that live event go viral and alter the course of history? Time will tell, but no one can deny the amazing reach and ability technological advances have provided to the learning, sharing and passing along of the stories and moments from those that came before us to those still yet to come.

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!