Perhaps you’ve visited New York’s famous High Line, the 1.45-mile-long greenway built on elevated train tracks. After the rise of trucking made the train line obsolete in the 1980s, sections were gradually demolished, until a non-profit group was formed in an effort to preserve and reuse the tracks as a public space.

Princeton has its own recreational areas that were once used for resources and transportation. These places played a critical role in the community and surrounding region. When times changed, they were repurposed in a variety of ways that are enjoyed by the public today,

Mountain Lakes Ice Company

In the days before electric refrigerators, the Princeton Ice Company (also known as the Mountain Lake Ice Co.) harvested ice from a man-made pond, delivering blocks to local homes and businesses by wagon. In 1883, Stephen Margerum, who was operating the Riverside Ice Company, purchased a small farm near the corner of Bayard Lane and Mountain Avenue. By damming streams on the property, he formed lakes, thus establishing what became a thriving family business; that is, until the invention of electric refrigerators for home use. As the technology was improved and widely accepted, the ice trade became obsolete. By 1930, the Mountain Lakes Ice Company was dissolved.

In 1987, Princeton Township bought the property for use as open space, now known as the Billy Johnson Mountain Lakes Nature Preserve. Twenty years later, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2013 the town received an Historic Preservation Award from the state for its $3 million rehabilitation of the dams. The preserve is a part of four hundred acres of protected public land that not only maintains diverse ecosystems for plants and animals, but also provides recreation in the form of an interconnected network of hiking and biking trails. The Mountain Lakes House, designed as a private residence by renowned architect Rolf W. Bauhan, is now the headquarters of Friends of Princeton Open Space (FOPOS), and can be rented for weddings and other special events.

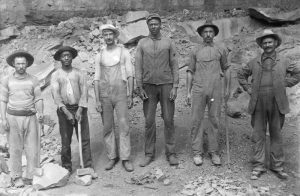

Margerum’s and McCarthy’s Quarries

In the early 20th century, at the end of Spruce Street, along both sides of Ewing Street (now Harrison Street), were two quarries that were sourced for stone to build many of Princeton’s iconic buildings. McCarthy Sons Quarry lay to the left, and Margerum Brothers Quarry to the right. (Stephen Margerum, owner of the Princeton Ice Company, also founded this company, which was passed down through three generations.)

In these quarries was a type of sedimentary rock called Lockatong argillite, which became known as “Princeton Stone.” This mud-rock became popular as a building material in New Jersey, particularly in Princeton and Lawrenceville, because of its hardness and durability. It could be used in structures, foundations, or crushed and made into concrete. Two distinct colors of stone were found in both quarries – a dark bluish gray and reddish brown to purplish hue.

When building the University’s Holder Hall (and the adjoining dining halls) from 1909-1911, architects Frank Day and Charles Klauder oversaw the selection and placement of the stone so that colors were properly blended, and sizes were harmonious. A cost-saving measure, the switch to using local stone from shipping schist from Wissahickon, PA reportedly saved twenty-five thousand dollars.

As an example of the importance of argillite to New Jersey’s history, in 1951, a piece of Princeton Stone was sent to Tennessee to be embedded in the masonry columns holding up a “Welcome to Gatlinburg” sign for its Chamber of Commerce. Each state contributed a native stone to the project.

By 1930, the area around the sites had developed residentially and the quarries were abandoned. For many years, once the quarry filled with groundwater, residents would go swimming in the summer and ice-skating in the winter. In 1978, thanks to the efforts of the Quarry Park Association, the former Margerum’s Quarry was developed as a passive recreational area. The Borough purchased 4.2 acres with a plan to preserve its natural features and include a bird-watching area, a picnic grove, game tables, and a playground. Recently approved was the inclusion of an off-leash dog park during morning hours.

By 1930, the area around the sites had developed residentially and the quarries were abandoned. For many years, once the quarry filled with groundwater, residents would go swimming in the summer and ice-skating in the winter. In 1978, thanks to the efforts of the Quarry Park Association, the former Margerum’s Quarry was developed as a passive recreational area. The Borough purchased 4.2 acres with a plan to preserve its natural features and include a bird-watching area, a picnic grove, game tables, and a playground. Recently approved was the inclusion of an off-leash dog park during morning hours.

A special corner of the park is designated “Maggie’s Playground,” in honor of Maggie McCormick, who died in 1988 at just 19 months old. The park was her favorite place in Princeton, according to her parents, Susan Lenz and Dean McCormick, who fundraised to create the enclosed playground for others to enjoy and create their own memories. New equipment and benches were installed in 2020.

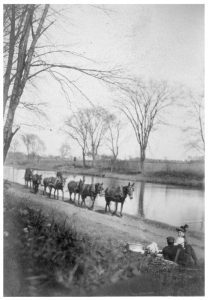

Delaware and Raritan Canal

Before railroads, the Delaware and Raritan Canal was built to be an efficient and reliable means to transport freight – especially coal – between Philadelphia and New York City. The idea of a canal between the two rivers had a long history, going back to William Penn, who suggested it in the 1690s. It would shorten the journey between the two cities by 100 miles and eliminate the need for boats to journey into the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1816, the New Jersey legislature created a three-person commission to survey and map out a proposed route, which went from New Brunswick, to Princeton, cutting through Trenton, to Bordentown. The charter for the D&R Canal was granted in 1830, with $1.5 million allocated for its construction. The majority of the work was completed by Irish immigrants, clearing land and digging the 75-foot-wide channel with hand tools; it was completed in just four years. Before steam power came into use, teams of mules were used to tow boats through the canal. Children as young as eight years old were employed as mule tenders, walking the animals along the towpath.

The canal’s usage peaked during the 1860s and 70s. As railroads – which served the same function, but more quickly and efficiently – grew in prominence, the canal became less important. The D&R Canal ceased operating at a profit in 1892 but remained open through 1932. The State of New Jersey took ownership four years later, and grassroots efforts were made to preserve and repurpose the waterway. In 1973, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and a year later, more than 60 miles were designated as an official state park. In the 1980s, a portion of the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad corridor from Bulls Island to Frenchtown was included, adding an additional 10 miles.

Today, the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park is one of Central New Jersey’s most popular recreational corridors. Hikers and cyclists can enjoy the flat, continuous path by land, while boaters can travel via canoes, kayaks, and paddleboards. A refuge for both nature and history lovers, opportunities abound for birdwatching, photography, fishing, and picnicking.

Today, the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park is one of Central New Jersey’s most popular recreational corridors. Hikers and cyclists can enjoy the flat, continuous path by land, while boaters can travel via canoes, kayaks, and paddleboards. A refuge for both nature and history lovers, opportunities abound for birdwatching, photography, fishing, and picnicking.

Thanks to the hard work and dedication of community members, these historical locations have been transformed into recreational areas for everyone to enjoy. Once no longer useful to industry, they were at risk for pollution or new construction; for many years, developers hoped to build condominiums or an underground parking garage at the quarry site. Next time you’re hiking in the Mountain Lakes Preserve, biking along the canal, or trying out the new dog park, take a moment to appreciate the preserved green space and imagine how different the landscape looked 100 years ago.

Eve Mandel is the Director of Programs and Outreach at the Historical Society of Princeton (HSP). She plans and teaches a variety of history programs for adults and students. Eve is also responsible for HSP’s community relations, managing all press, social media and public relations, as well as building collaborations with other non-profits and service organizations.