Is there a place in town that you’ve always wondered about? A story you’ve heard that you just can’t believe to be true? There are many superstitions and historical renditions that people enjoy sharing but often haven’t verified. Princeton Perspectives is now revealing the details behind many of Princeton’s most popular sources of gossip.

Library House(s)

Is it one house or two? Situated at 94 and 104 Library Place are in fact two homes that have become fodder for a lot of conversation. If you’ve ever traveled along Library Place, from Hodge Road toward 206/Stockton Street, a street filled with large properties and grand homes, you likely noticed two of the beautiful homes on the right that sit very close to each other and look shockingly similar. At certain angles, when the trees are in bloom, they actually look like one house, with the greenery making it hard to see about 12 feet of space that sits between the two.

Is it one house or two? Situated at 94 and 104 Library Place are in fact two homes that have become fodder for a lot of conversation. If you’ve ever traveled along Library Place, from Hodge Road toward 206/Stockton Street, a street filled with large properties and grand homes, you likely noticed two of the beautiful homes on the right that sit very close to each other and look shockingly similar. At certain angles, when the trees are in bloom, they actually look like one house, with the greenery making it hard to see about 12 feet of space that sits between the two.

Even local real estate agents aren’t quite sure what the story is. Some believe they are two similar homes that were built by the same builder. Others are confident they were once one home that was split into two. Of those that believe the latter, there are varying rumors for the split – a couple got divorced and neither was willing to give up the house, so they split it; two brothers got the house after their parents’ death and things grew bitter, so they separated it into two. None of the above happen to be the true story.

Last summer a young couple, Aditya Rajagopalan and Alston Gremillion, bought their new home at 104 Library Place. They quickly became eager to understand why all their friends in the area called it “the house cut in half.” For a Christmas gift, Alston’s father, Mark Gremillion, put together a family tree and historical information on the house, which ultimately revealed the little-known tale.

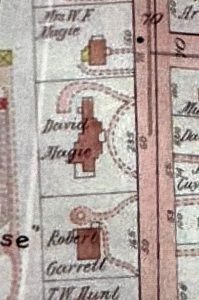

It was discovered that land was purchased, and one single house was built on it from 1901-1903, first inhabited by Dr. David Magie and then just his wife until she sold it in 1924. Estelle Frelinghuysen then bought it and lived there until her death in 1931. That was during the Great Depression, followed by World War II. So, Frelinghuysen’s house sat empty for 13 years until 1944 when the estate was settled and sold to Holder Corporation. Holder felt people were not buying homes of that size at the time and the best way to get it sold was to cut the house in half, into two “smaller” homes. The truth lacks a bit of the drama some of the gossip holds, but it is still a fascinating turn of events.

“They literally just removed a section in the middle,” she explains. “If you walk between the two houses, you can see stucco on either side between them. The other three sides of each house are stone.”

Princetonian’s did witness first-hand how one home can be moved to another lot, when the building on 91 Prospect was moved across the street earlier this year. But, seldom, if ever, has anyone around recently witnessed one home get split into two. To confirm it started as one house, you can see the original home in this old photo and the land map from that time also displays one house on the lot where the two homes sit today.

Princetonian’s did witness first-hand how one home can be moved to another lot, when the building on 91 Prospect was moved across the street earlier this year. But, seldom, if ever, has anyone around recently witnessed one home get split into two. To confirm it started as one house, you can see the original home in this old photo and the land map from that time also displays one house on the lot where the two homes sit today.

FitzRandolph Gate

Princeton University architecture has been the source of many stories. You can’t really miss its FitzRandolph Gate, the black iron gate with tall columns alongside Nassau Street, at the intersection of Witherspoon Street. But have you ever walked through it? If so, did you think about how your path might determine your destiny?

Princeton University architecture has been the source of many stories. You can’t really miss its FitzRandolph Gate, the black iron gate with tall columns alongside Nassau Street, at the intersection of Witherspoon Street. But have you ever walked through it? If so, did you think about how your path might determine your destiny?

Built in 1905, FitzRandolph Gate was erected outside Princeton University’s Nassau Hall to honor Nathaniel FitzRandolph, the man primarily responsible for raising the funds used to purchase the college’s first plot of land in Princeton. The gate was kept closed and locked for decades, opened only during special occasions, and was meant to separate the town from the college. But in the 1970s, it was opened permanently, allegedly as a gesture to open the doors of the university to the town and the world.

Since then, it has been the center of a longtime superstition. Be careful where you go! Legend has it that any undergraduate that exits campus through the center gate (entering is said to be safe) will not graduate. The myth first was believed to have meant you wouldn’t graduate at all, though some interpret it to mean one simply would not graduate on time.

The tradition of avoiding the center entrance is passed along through students from year to year. You will often see them purposefully make their way to one of the side exits rather than go through the center. Princeton University is unable to verify any legitimacy to this myth, though there have been several students who’ve alleged to have walked through on purpose or by accident, and still graduate as expected.

Drumthwacket

What is this “white house” that sits on State Highway 206N, between Lawrenceville and downtown Princeton? Many people think it is just another extravagant Princeton home but it is in fact Drumthwacket, the grand estate that has been the NJ Governor’s mansion for decades. Where did the name Drumthwacket come from and how did this property come to be?

What is this “white house” that sits on State Highway 206N, between Lawrenceville and downtown Princeton? Many people think it is just another extravagant Princeton home but it is in fact Drumthwacket, the grand estate that has been the NJ Governor’s mansion for decades. Where did the name Drumthwacket come from and how did this property come to be?

On land once owned by William Penn, the home was built in 1835 by Charles Smith Olden, the man who would later become Governor from 1860-1863. He’d purchased this land from his grandfather, Thomas Olden (the small farmhouse now called Thomas Olden House, where Charles was born, had already been built there). After Olden’s death, the land and properties were purchased from his widow by Moses Taylor Pyne, who added onto the main house to grow the estate. Under Pyne, the east and west wings were built, and the property filled in with ponds, gardens and recreational areas. The estate was bequeathed to Pynes’ granddaughter, Agnes, who then sold it to Abram Nathanial Spanel. The inventor, scientist and the last private owner founded what became Playtex, and designed the Apollo spacesuit.

Drumthwacket, was purchased from the Spanels by the state of NJ in 1966, with the intent it become the governor’s residence. But that didn’t officially happen for decades, when funds were raised, and it was properly maintained. It kept its name, though – Drumthwacket – the name given to the home by Charles Smith Olden when he built it. It is believed he took the name from an old novel by Sir Walter Scott’s popular, A Legend (of the Wars) of Montrose, a Scots-Gaelic name that translates to mean “wooded hill.”

Surprisingly, with all that allure and stature, Drumthwacket has only been the full-time residence for 3 sitting governors, Olden (before it was owned by NJ) and then James Florio (1990-1994) and Jim McGreevey (2002-2004). While recovering from a car accident, Governor Corzine also briefly stayed there in 2007.

Einstein

“Imagination is more important than knowledge,” said Albert Einstein. But he likely never imagined people would be taking pictures and stopping by his house 68 years after his death! Perhaps the world’s most famous mathematician, Einstein lived in this house at 112 Mercer Street until he passed in 1955. Though many correctly affiliate him with the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), there is often a misconception that he also worked as a professor at Princeton University (PU). He did not.

“Imagination is more important than knowledge,” said Albert Einstein. But he likely never imagined people would be taking pictures and stopping by his house 68 years after his death! Perhaps the world’s most famous mathematician, Einstein lived in this house at 112 Mercer Street until he passed in 1955. Though many correctly affiliate him with the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), there is often a misconception that he also worked as a professor at Princeton University (PU). He did not.

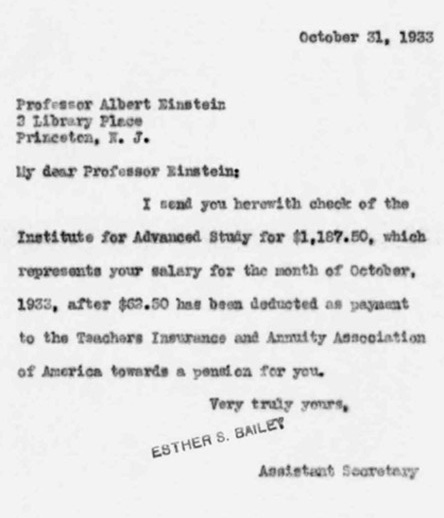

Is there a PU connection? Yes, there is, but he was never a professor there. When Einstein first came to visit Princeton in 1921, he delivered 5 lectures at PU and received an honorary degree. It wasn’t until the early 1930s that Abraham Flexner, the Founding Director of the Institute for Advanced Study, contacted Einstein back in Germany inviting him to come back and be amongst the first faculty to pursue self-directed research there. Einstein accepted and came in 1933, at a time of Nazi uprising in Germany. He feared for reprisals here in America so when he arrived, plans were made to bring him to town quietly and without fanfare. This letter, dated October 1933, confirms his first salary payment from IAS.

Where there is further confusion is that during his first six years with IAS (1933-1939), PU provided office space on campus at Fine Hall for Einstein and other Institute Faculty and School of Mathematics members. Though he may have given a further lecture at PU, he was never considered faculty there.

Upon Einstein’s death, this house was willed to Einstein’s stepdaughter. When she passed in 1986, it was left to the Institute.

Welcome to Princeton

When you drive into Princeton, have you ever taken notice of the sign welcoming you in? Turns out not everyone finds it so welcoming.

When you drive into Princeton, have you ever taken notice of the sign welcoming you in? Turns out not everyone finds it so welcoming.

Princeton’s Civil Rights Commission officially brought up issue with the signs and made their case before Princeton Council at a recent April meeting, citing that the words “Settled 1683” are not inclusive of the Lenape people who lived here before that time. The discussion had been ongoing, with some residents suggesting new signs should be made to either pay tribute to the initial inhabitants, the consolidation or not have a date on it at all.

If you’re a stickler for words, then the term “settled” is a point that has some disagreeing with those residents and the commission, having pointed out that settling often refers to when one establishes land ownership. The Lenape were a nomadic people, and while they lived on much of the land known today as Princeton, they moved around often depending on the seasons.

If one agrees that settling equals land ownership, then 1683 is the correct verbiage. It was that year that Henry Greenland became the first European property owner in what eventually became Princeton, according to Historical Society of Princeton. In that same vein, to the north and south of Princeton, Montgomery’s sign says “Founded circa 1702” and Lawrence signs say “Founded 1697.”

Princeton Council heard the commission’s presentation last month, and many seemed to agree with the concerns and are open to considering something different. Shall the sign honor the Lenape in some way, should it make note of the consolidation of the township and borough in 2013, or something else entirely? Some around town are saying there is time and money better well spent and the signs should be left alone.

Municipal staff is currently working with the Civil Rights Commission to come up with replacement costs and new signage ideas, at which point it will be brought back to Council for further discussion.

Now gossip!

So, now you know the stories. You can now drive around town, past the gate, the sign and all of the homes and people mentioned here and know just a little bit more about how they came to be. Consider yourself a true Princeton insider! Share this information (or better yet, this entire article) to help ensure the true stories are passed along.

Lisa Jacknow spent years working in national and local news in and around New York City before moving to Princeton. Working as both a TV producer and news reporter, Lisa came to this area to focus on the local news of Mercer County at WZBN-TV. In recent years, she got immersed in the Princeton community by serving leadership roles at local schools in addition to volunteering for other local non-profits. In her free time, Lisa loves to spend time with her family, play tennis, sing and play the piano. A graduate of the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Lisa was raised just north of Boston, Massachusetts but has lived in the tri-state area since college. She is excited to be Editor and head writer for Princeton Perspectives!

Ingredients:

Ingredients: Ingredients (4-5 servings)

Ingredients (4-5 servings)

Ingredients:

Ingredients: